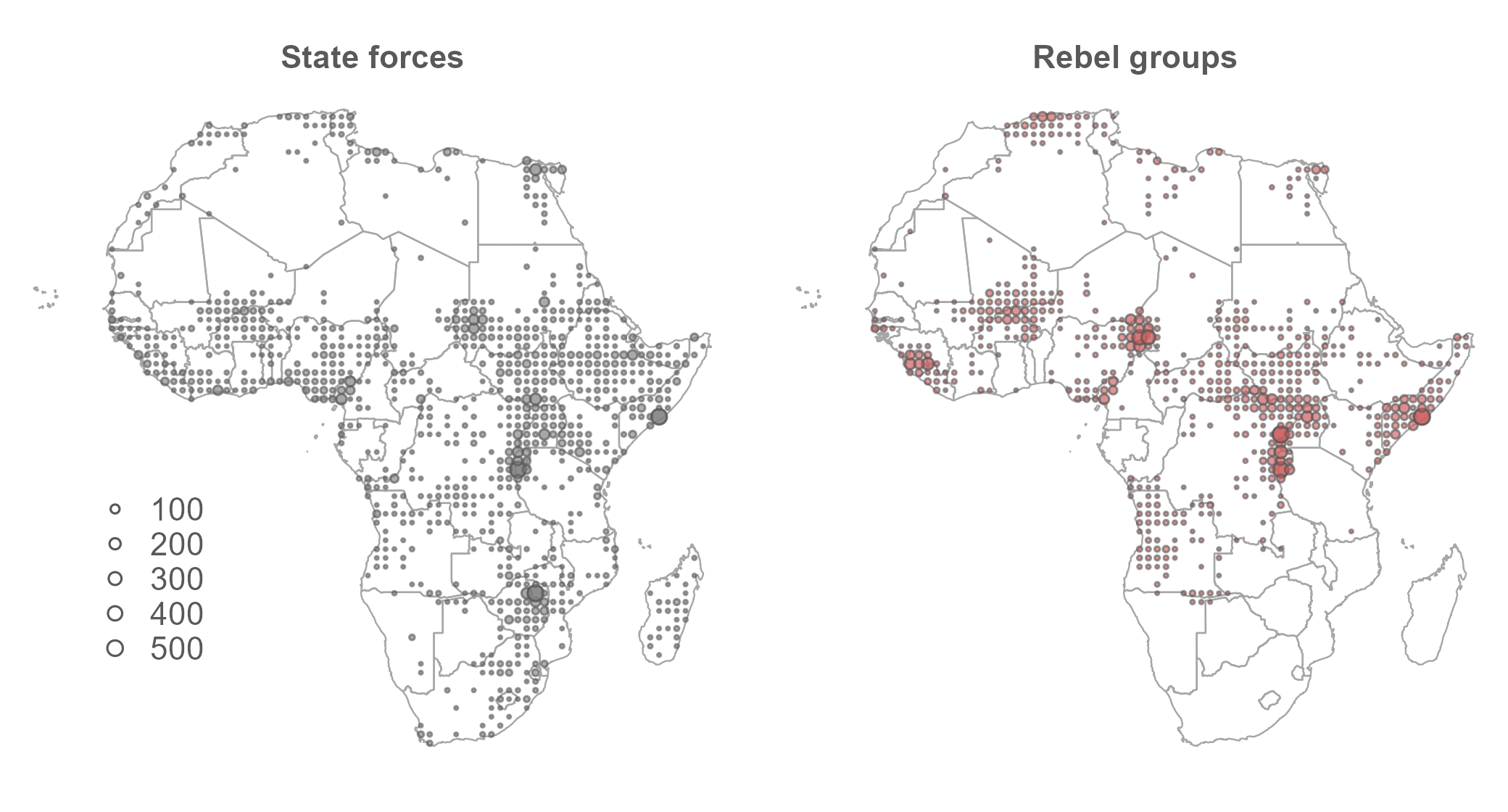

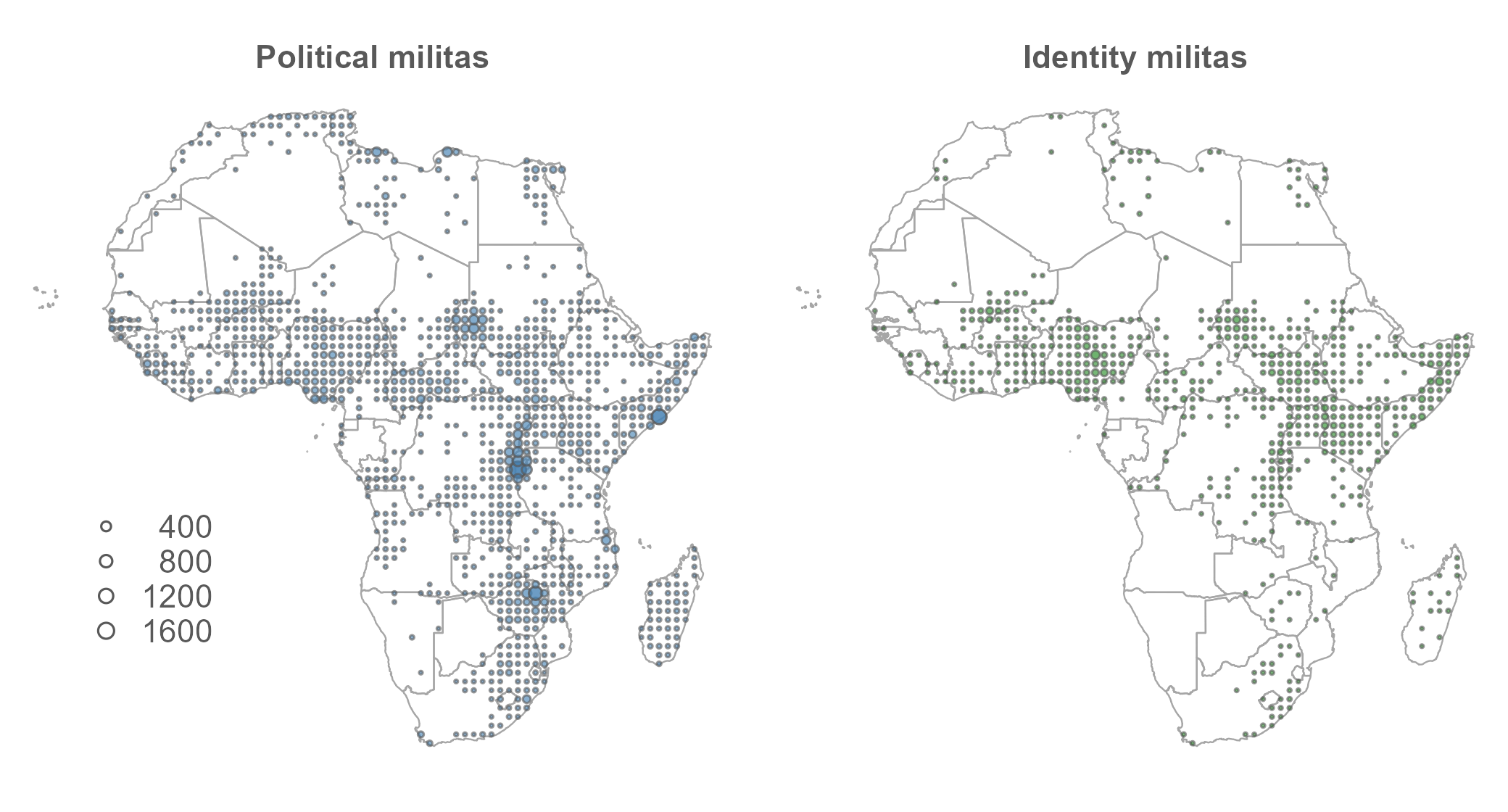

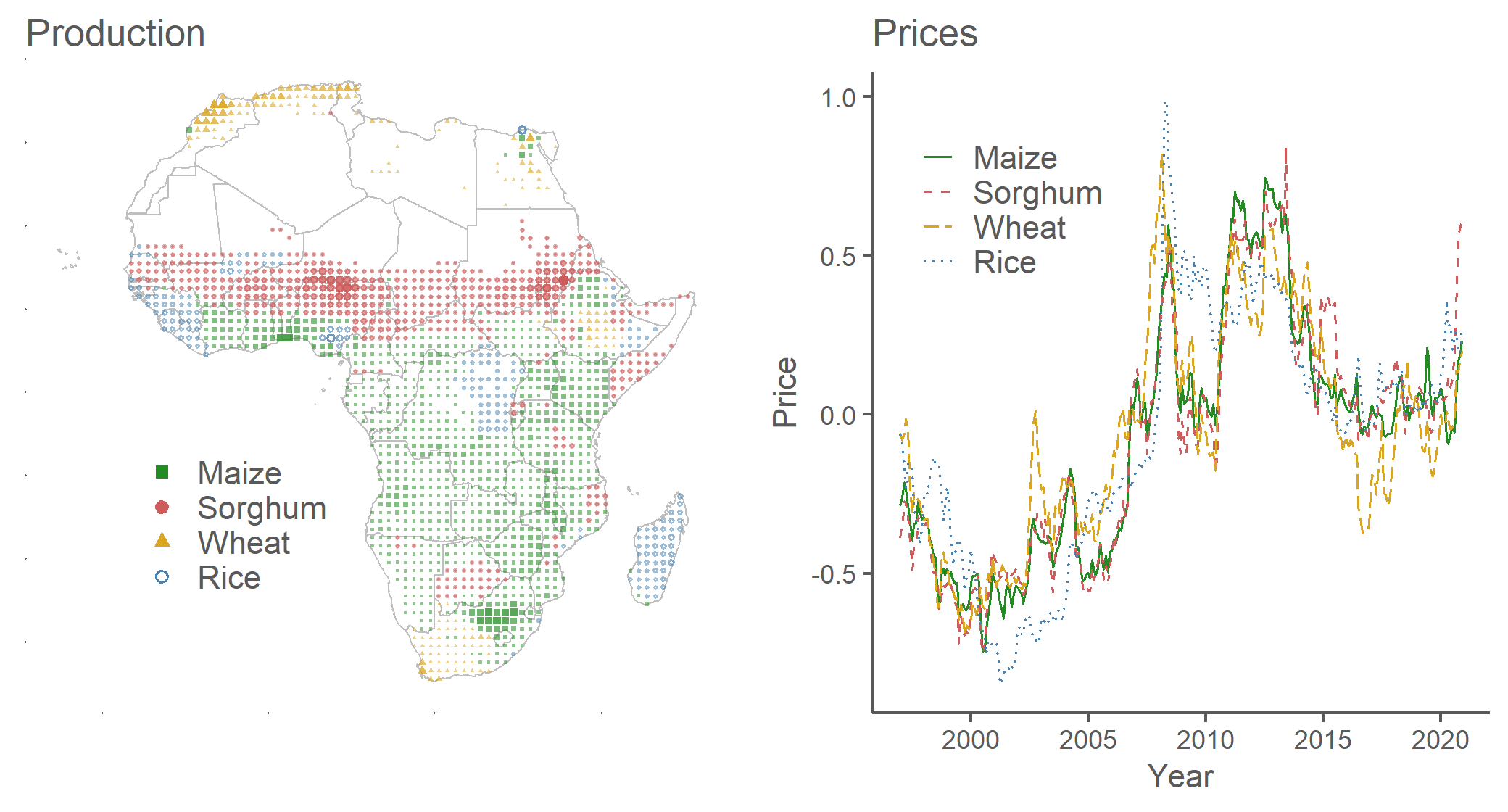

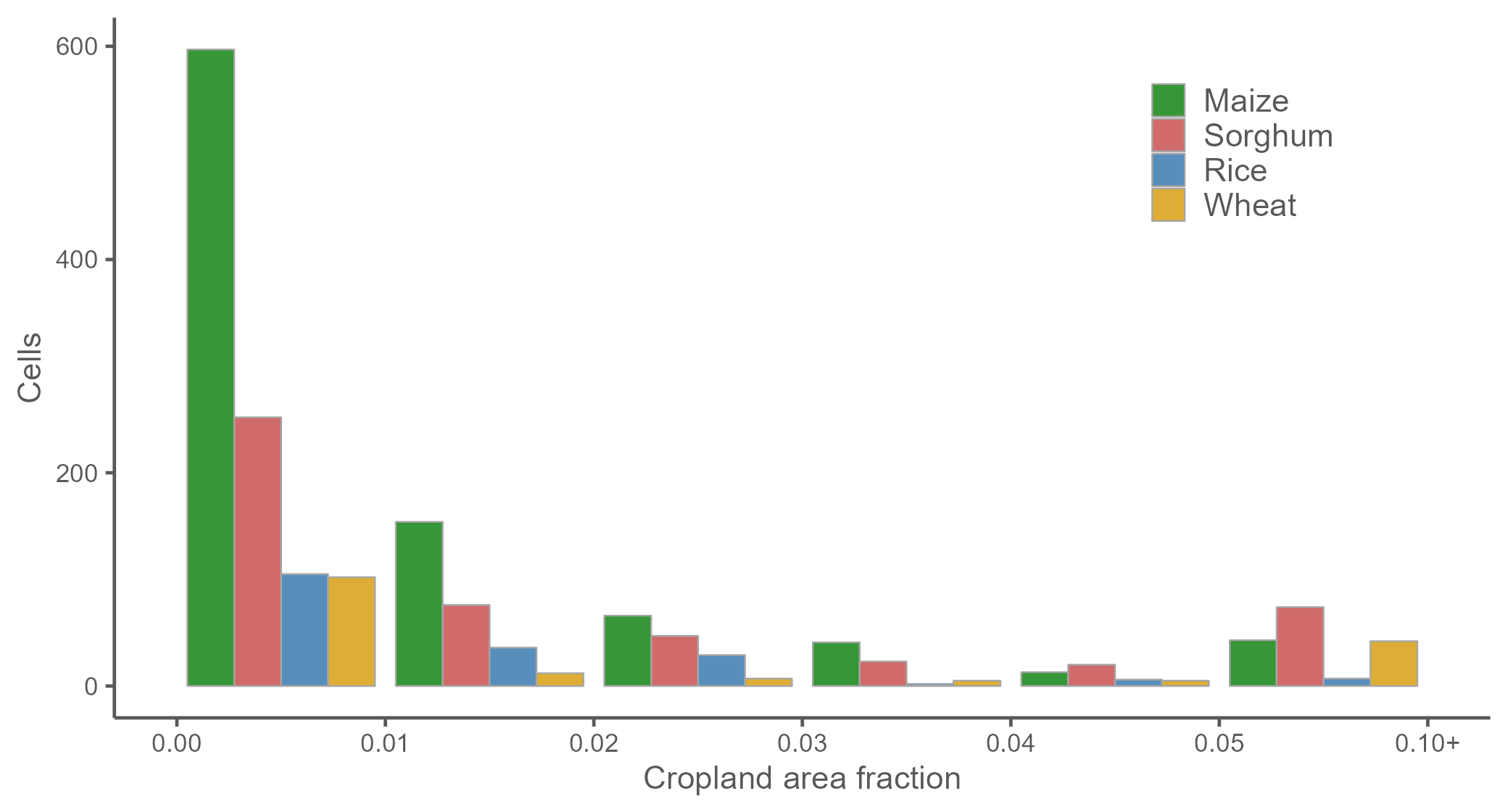

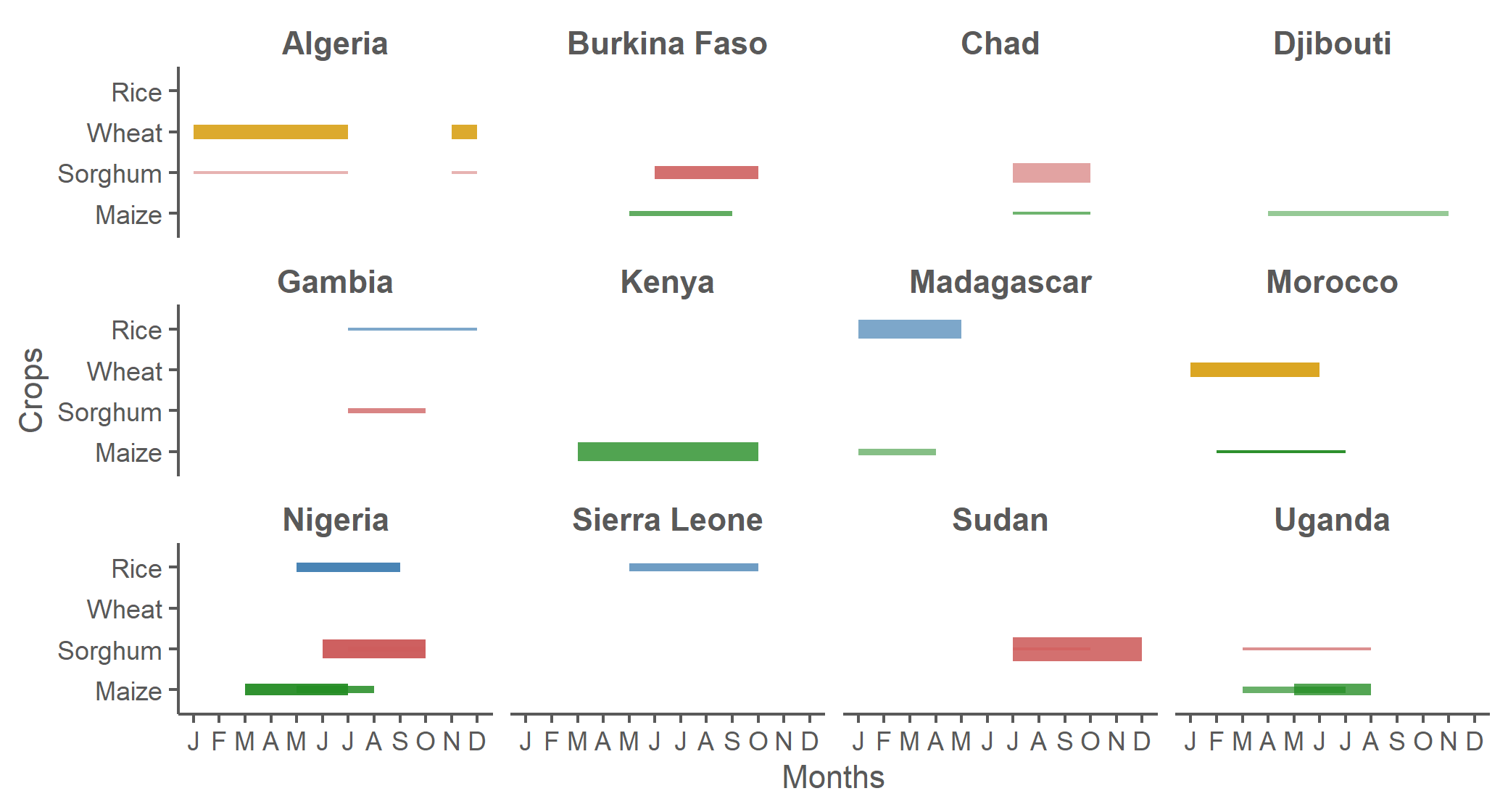

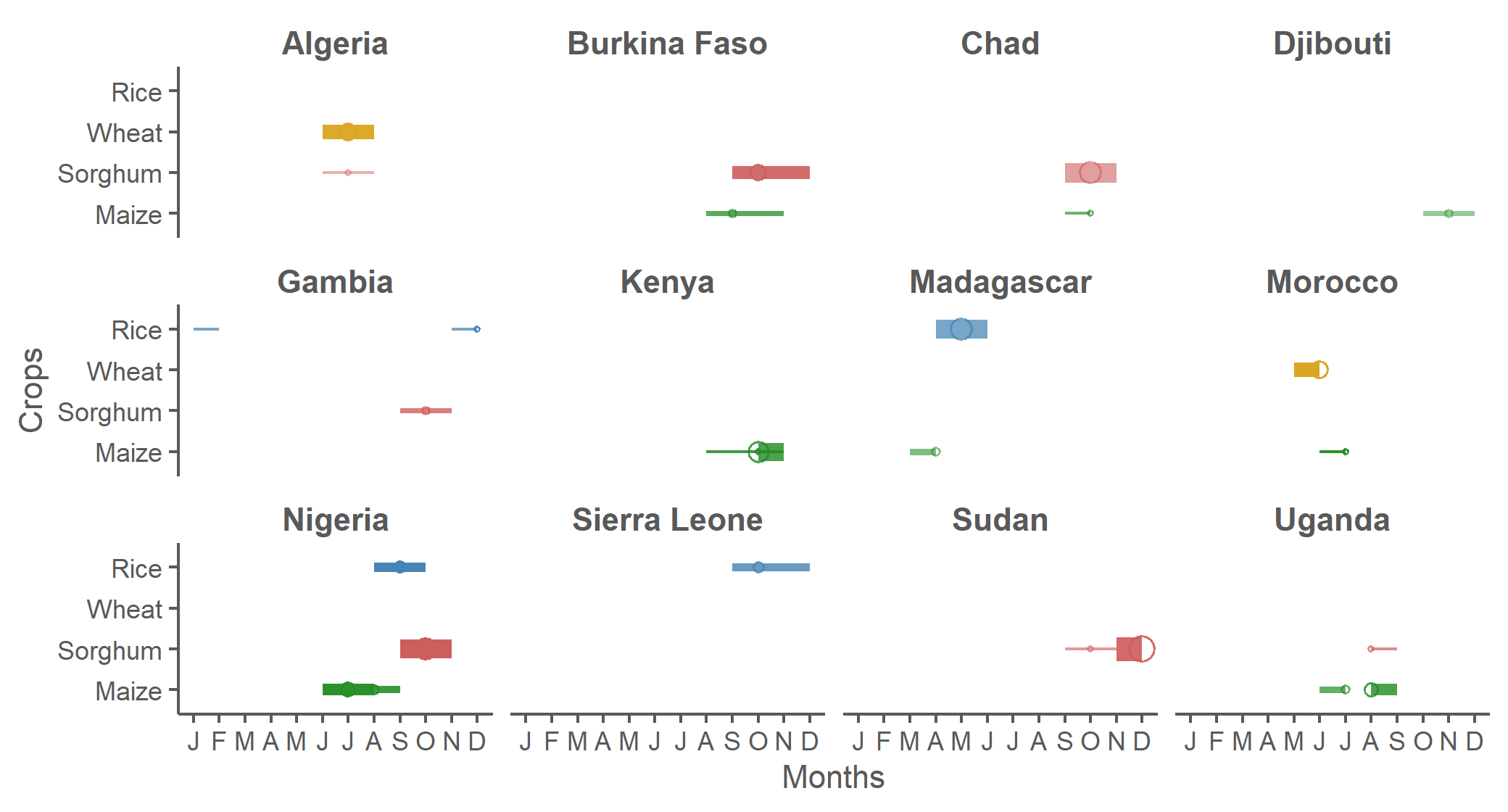

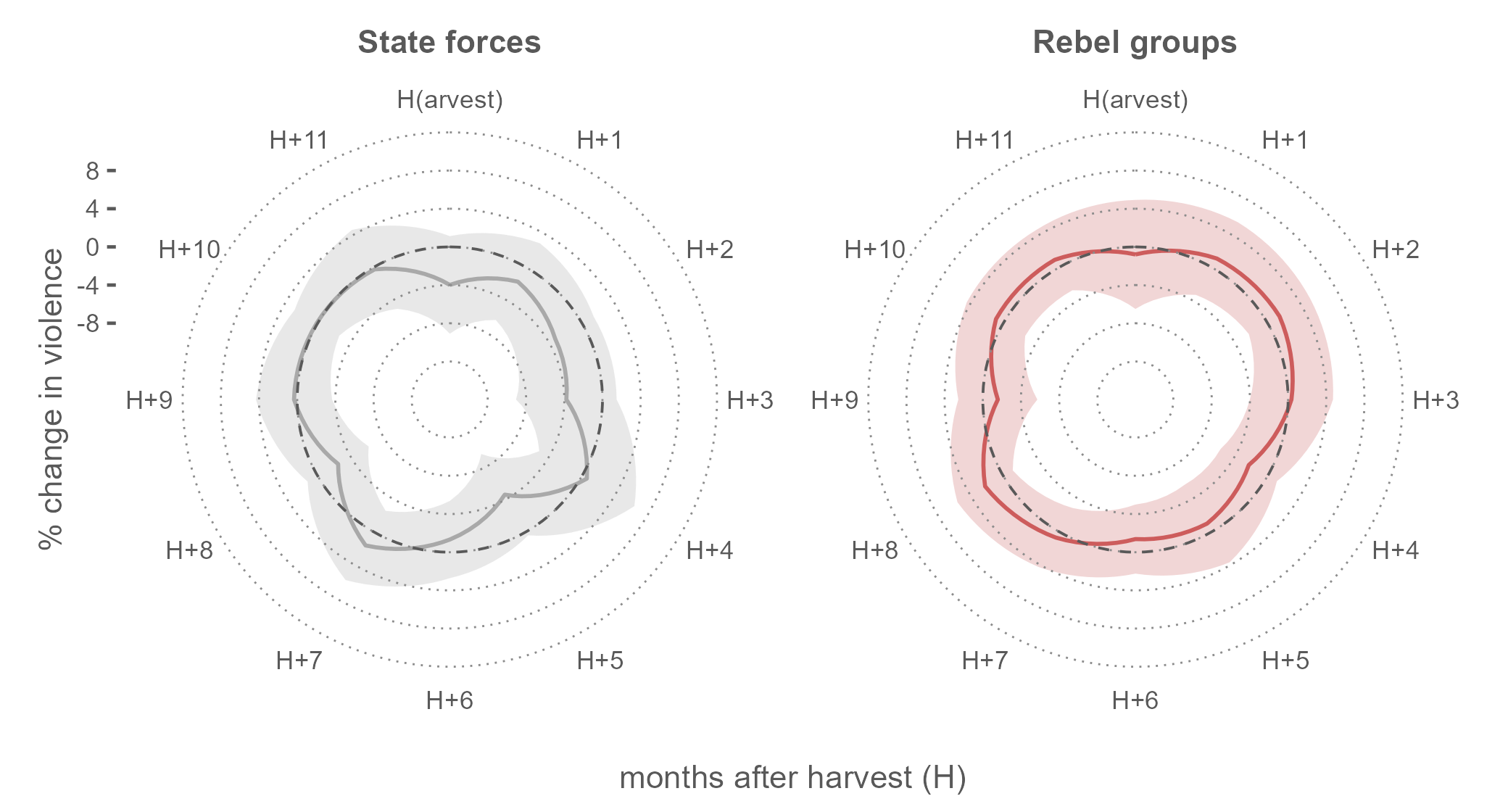

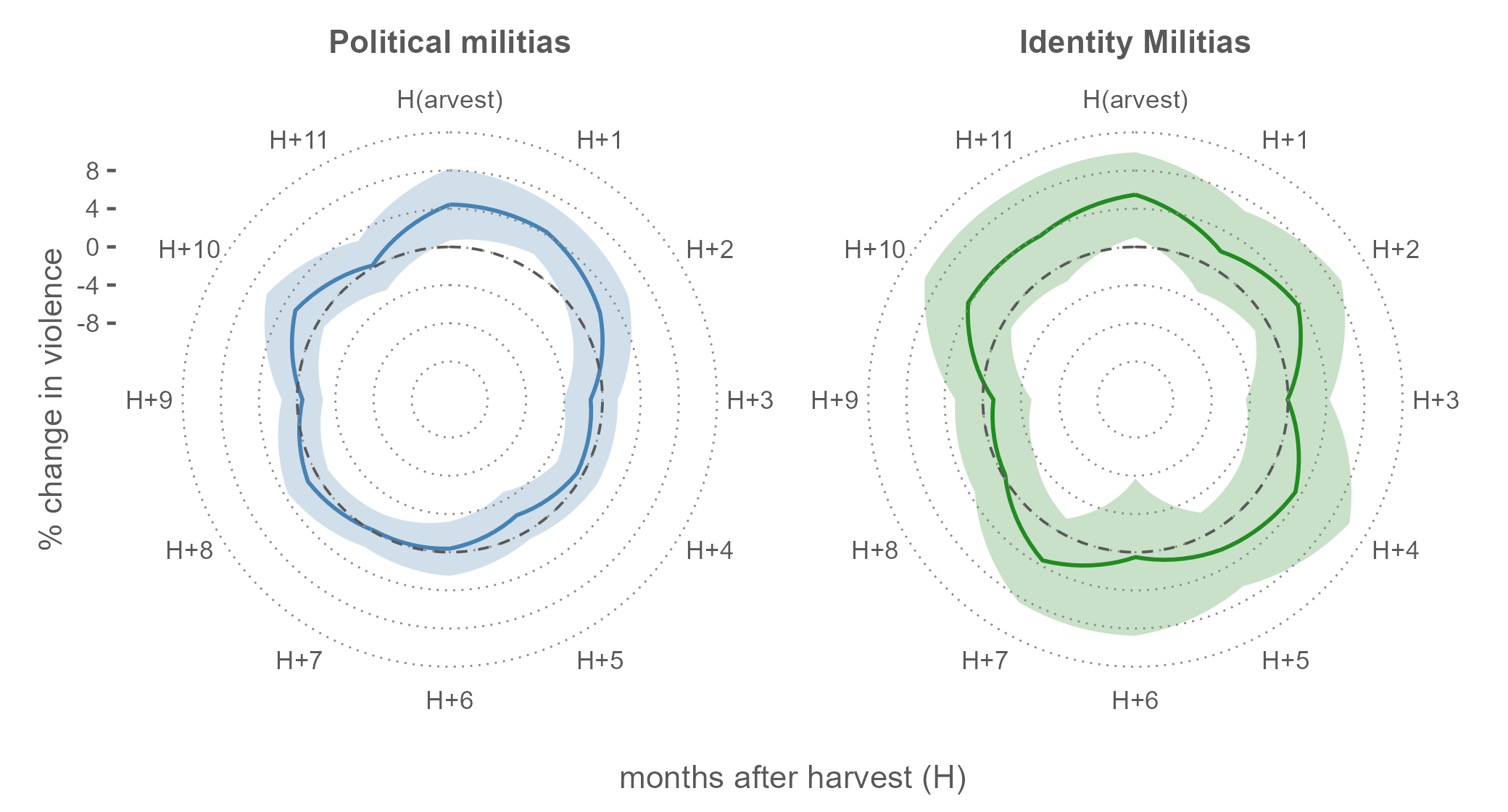

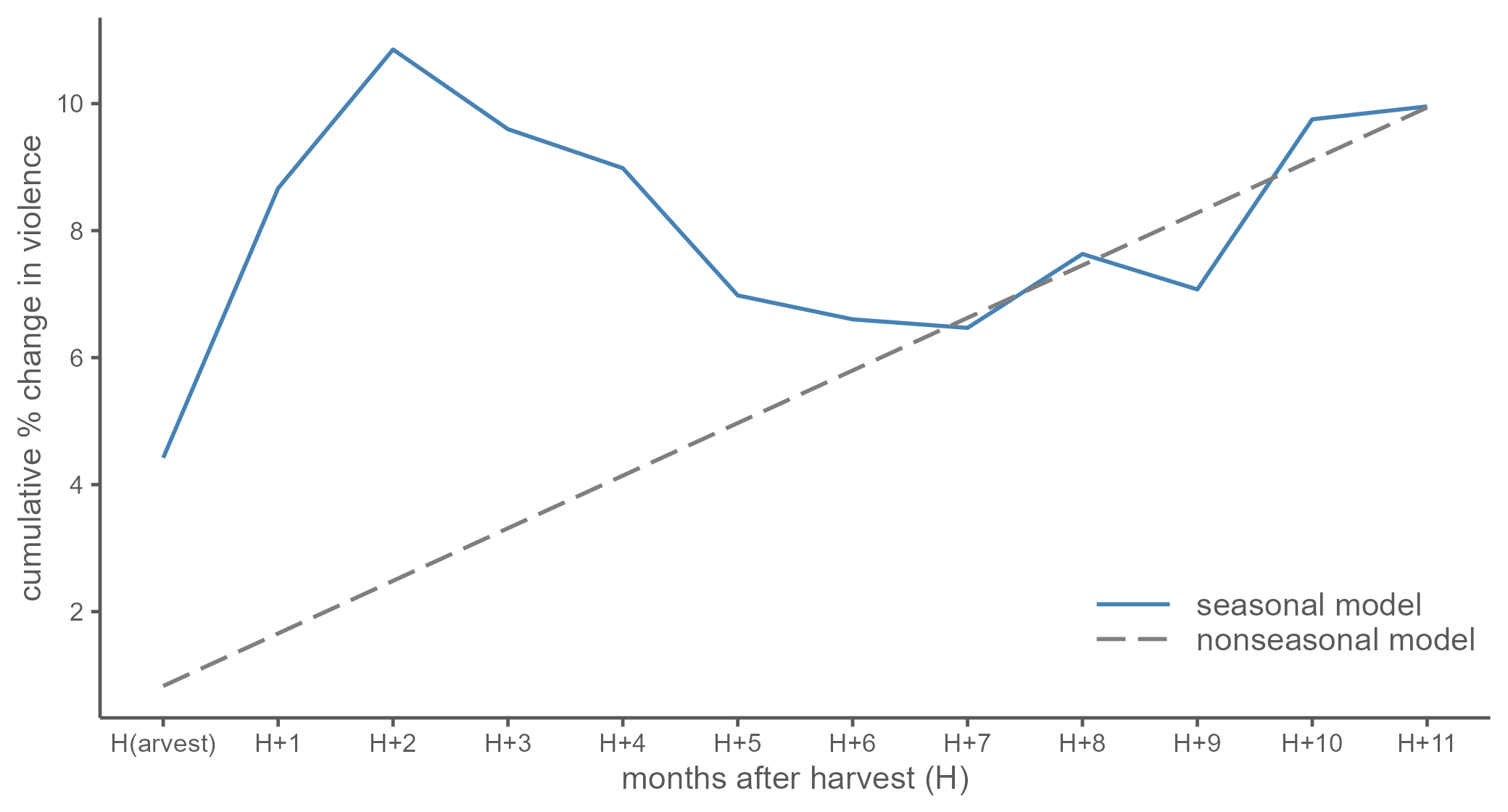

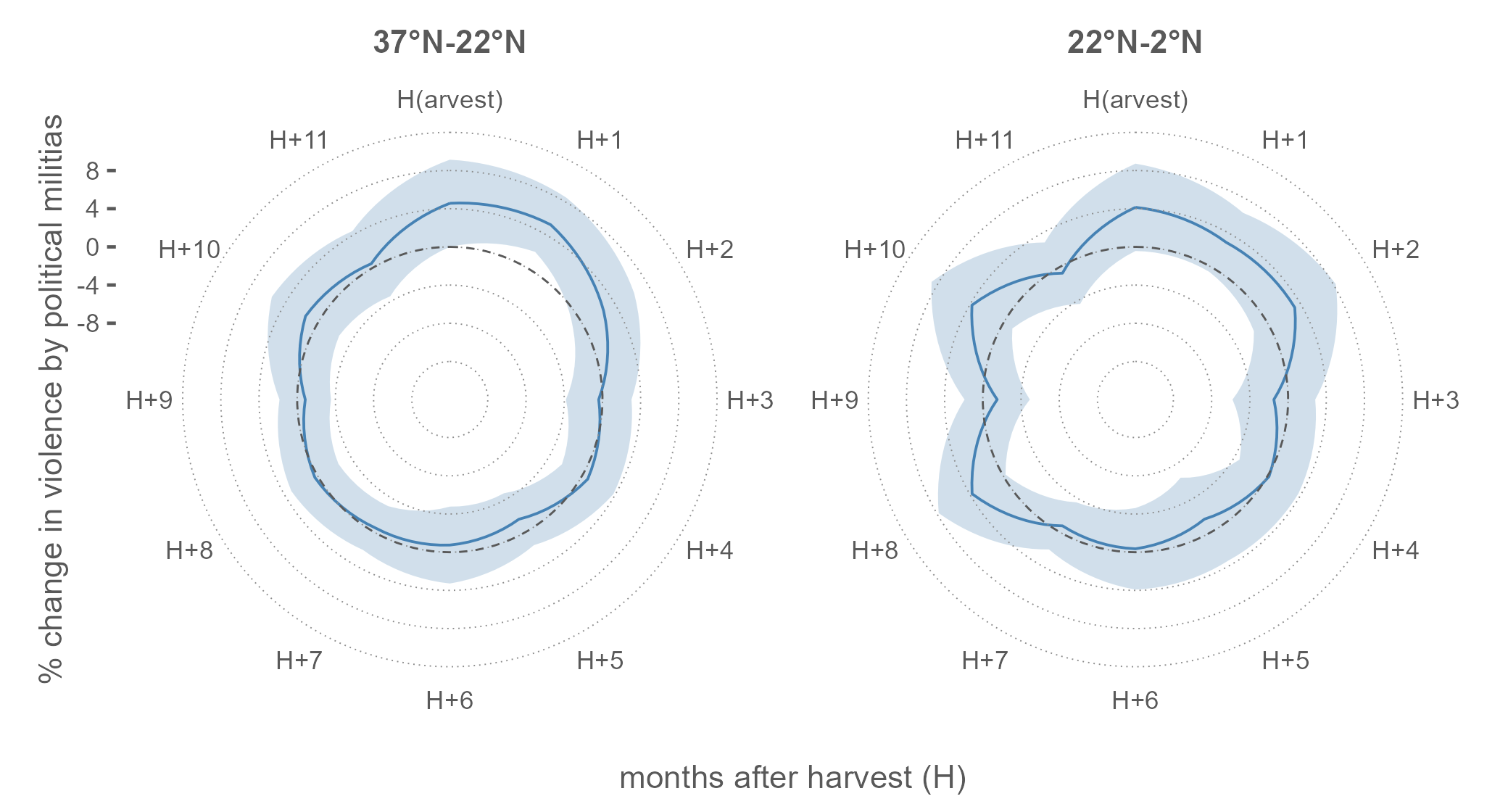

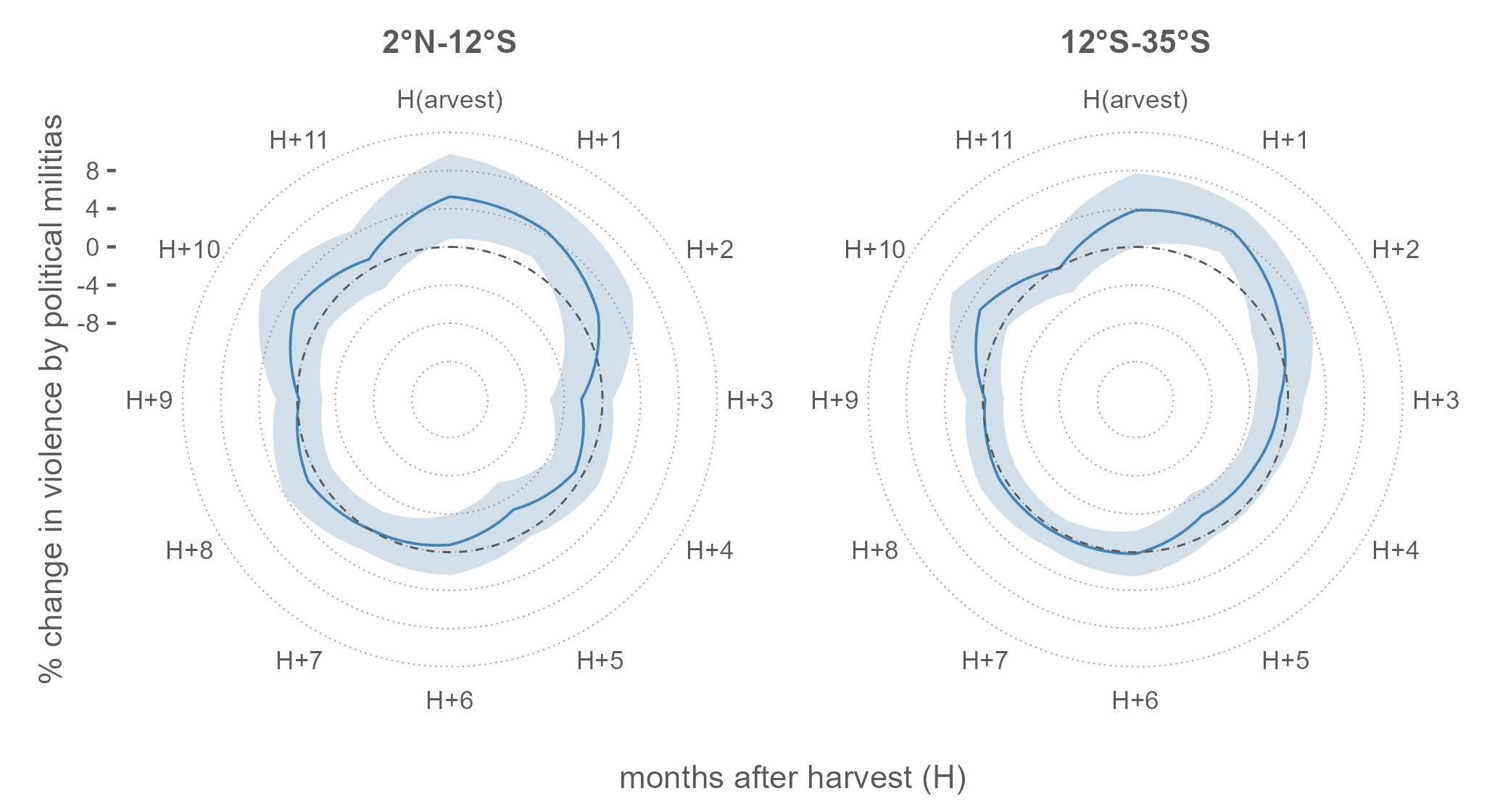

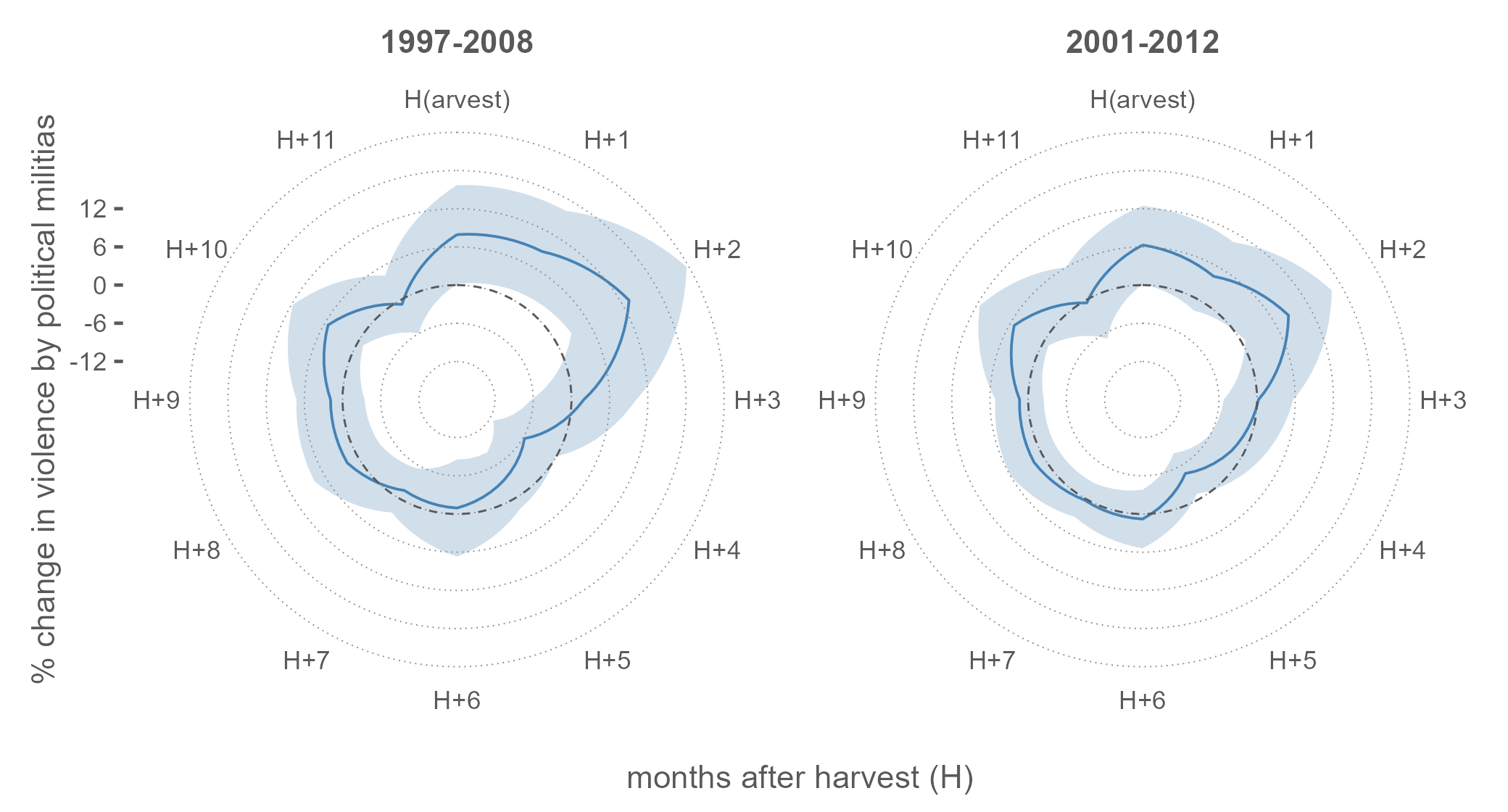

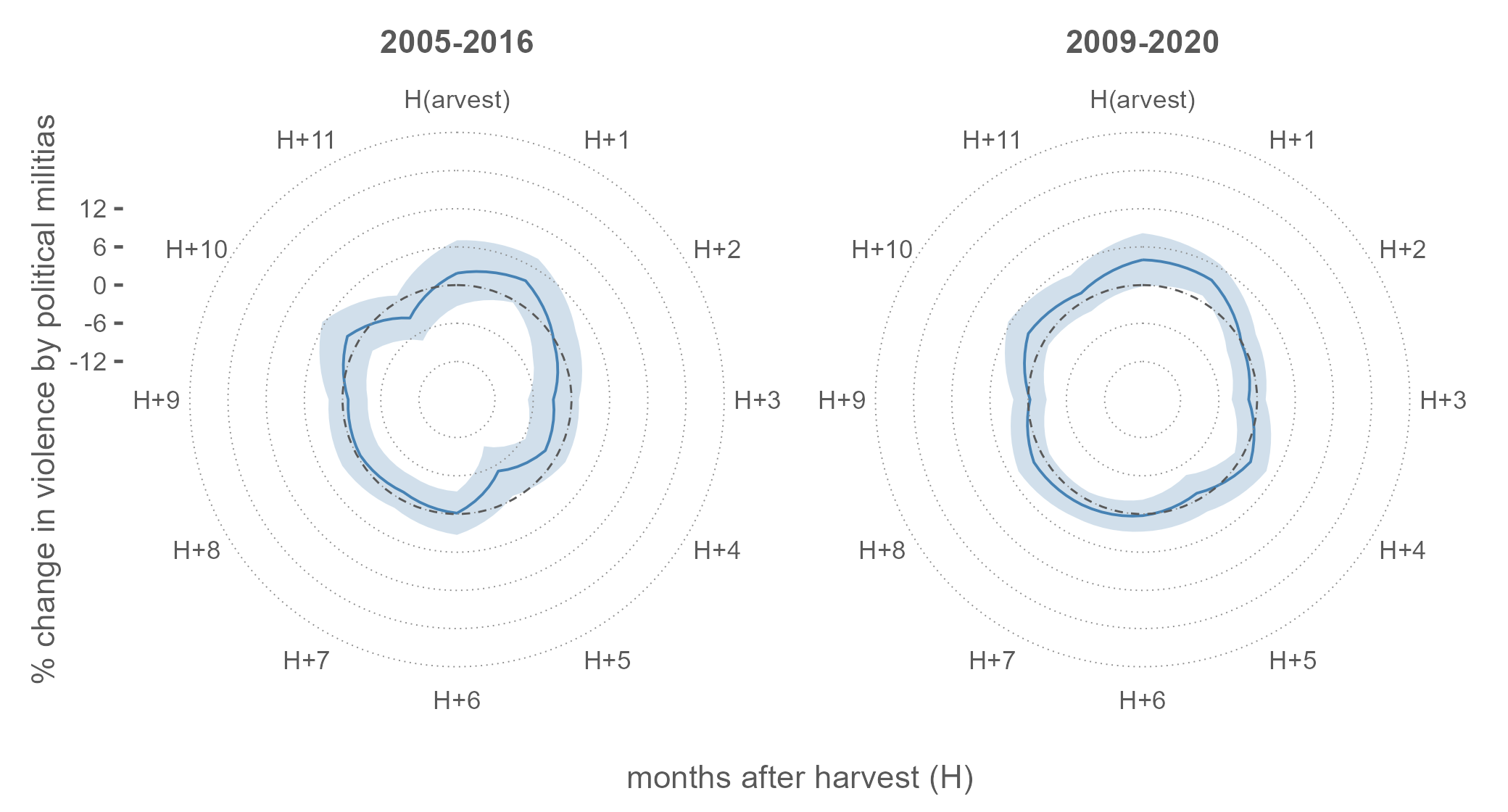

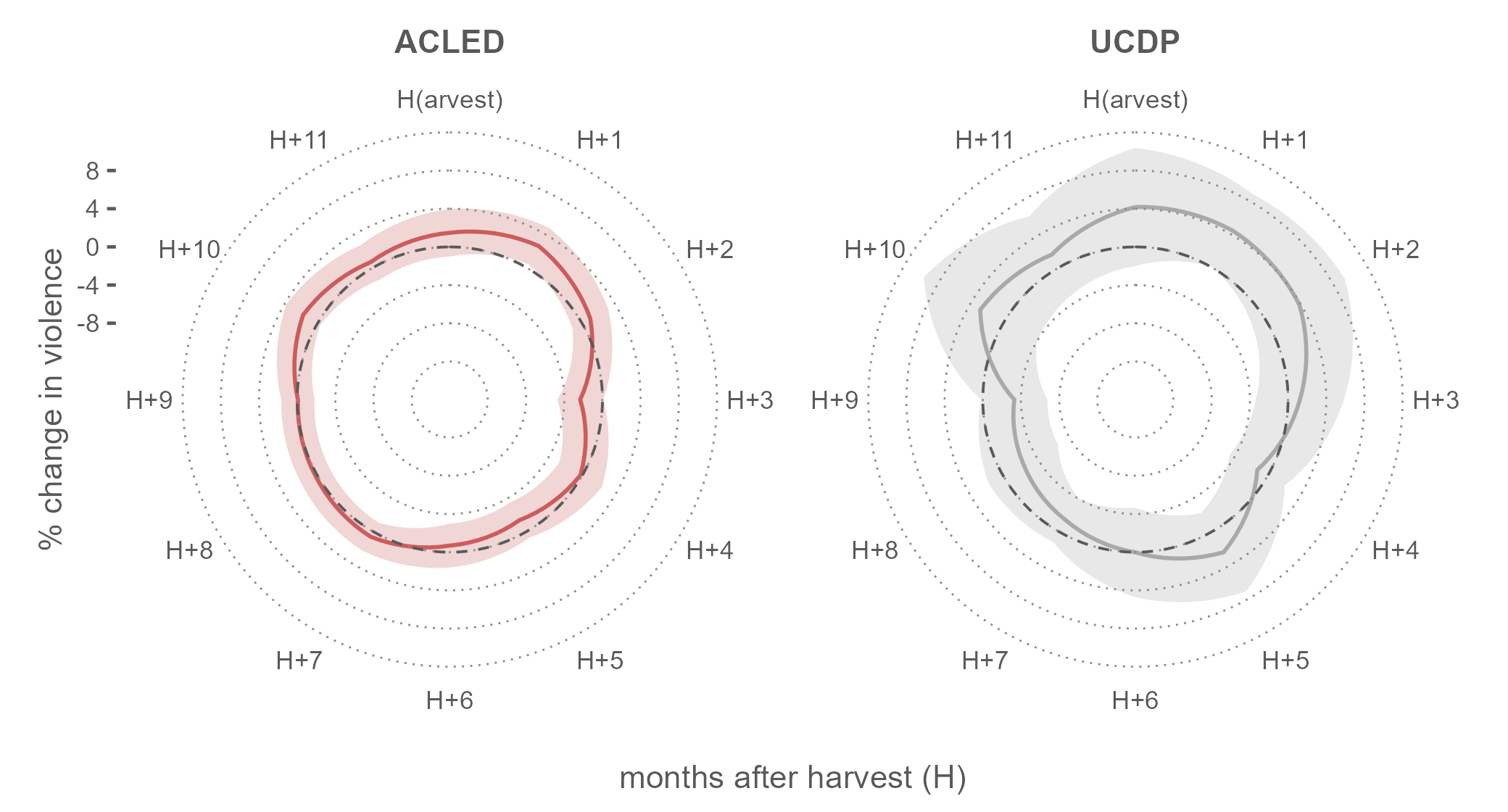

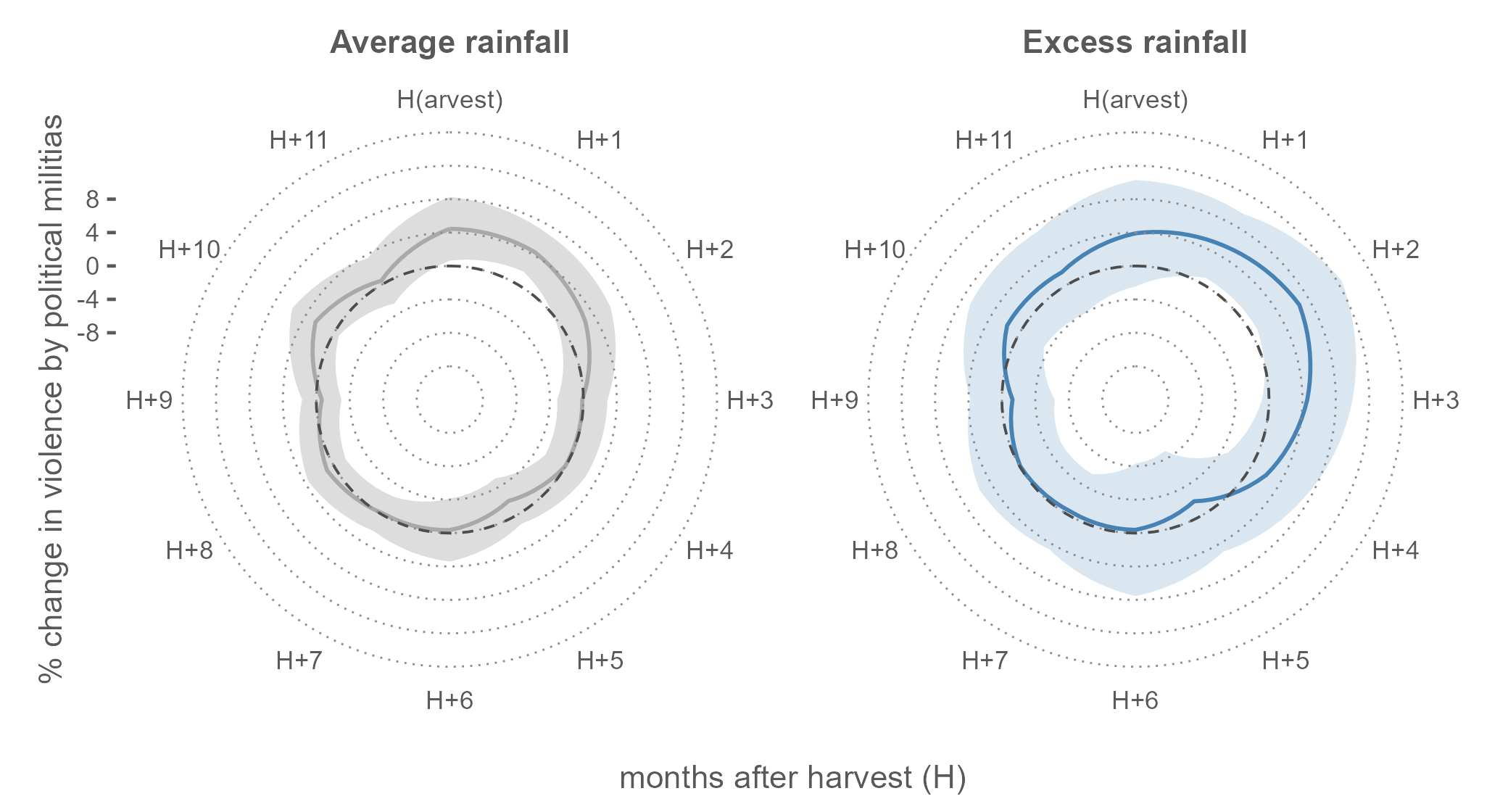

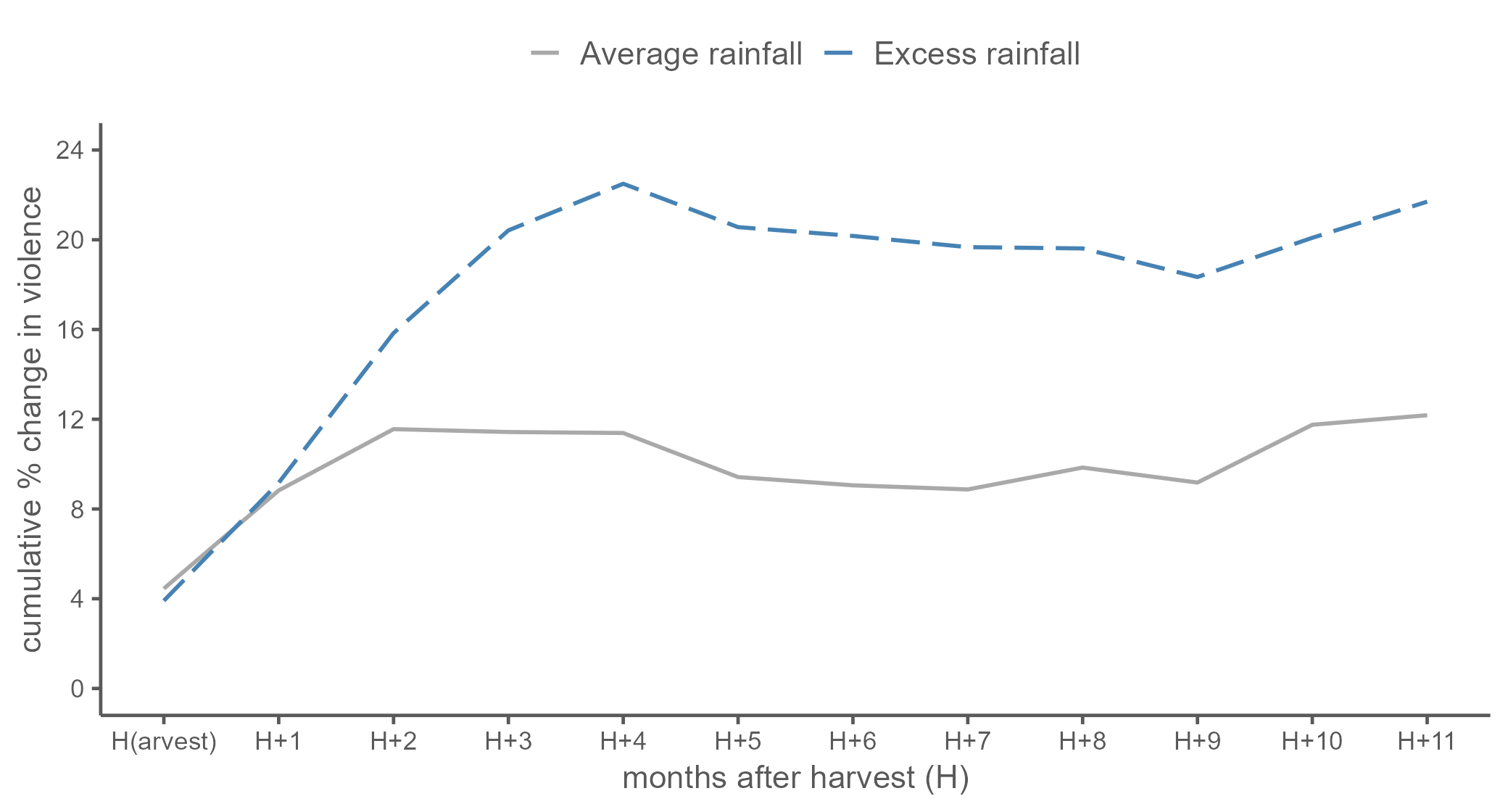

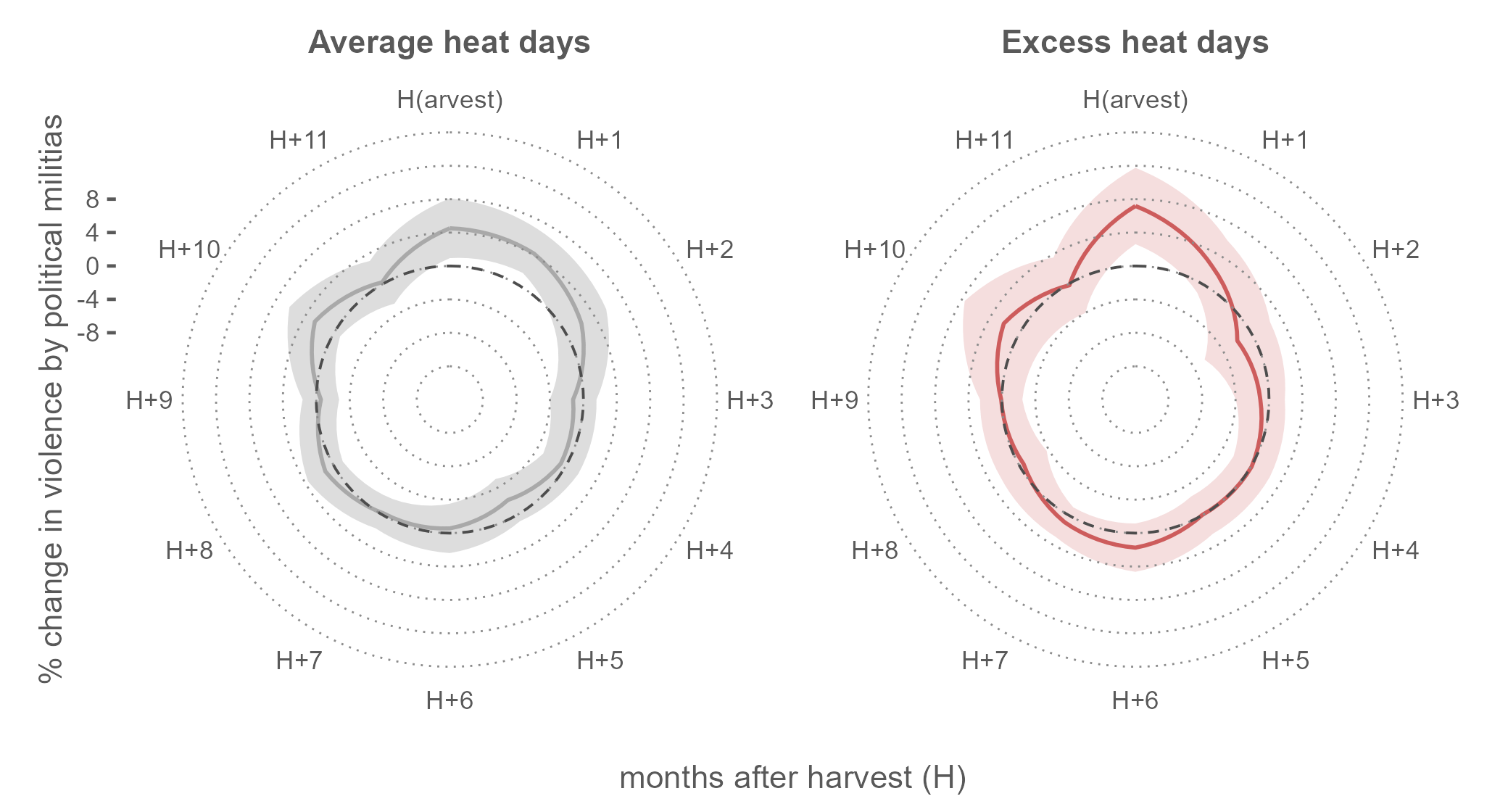

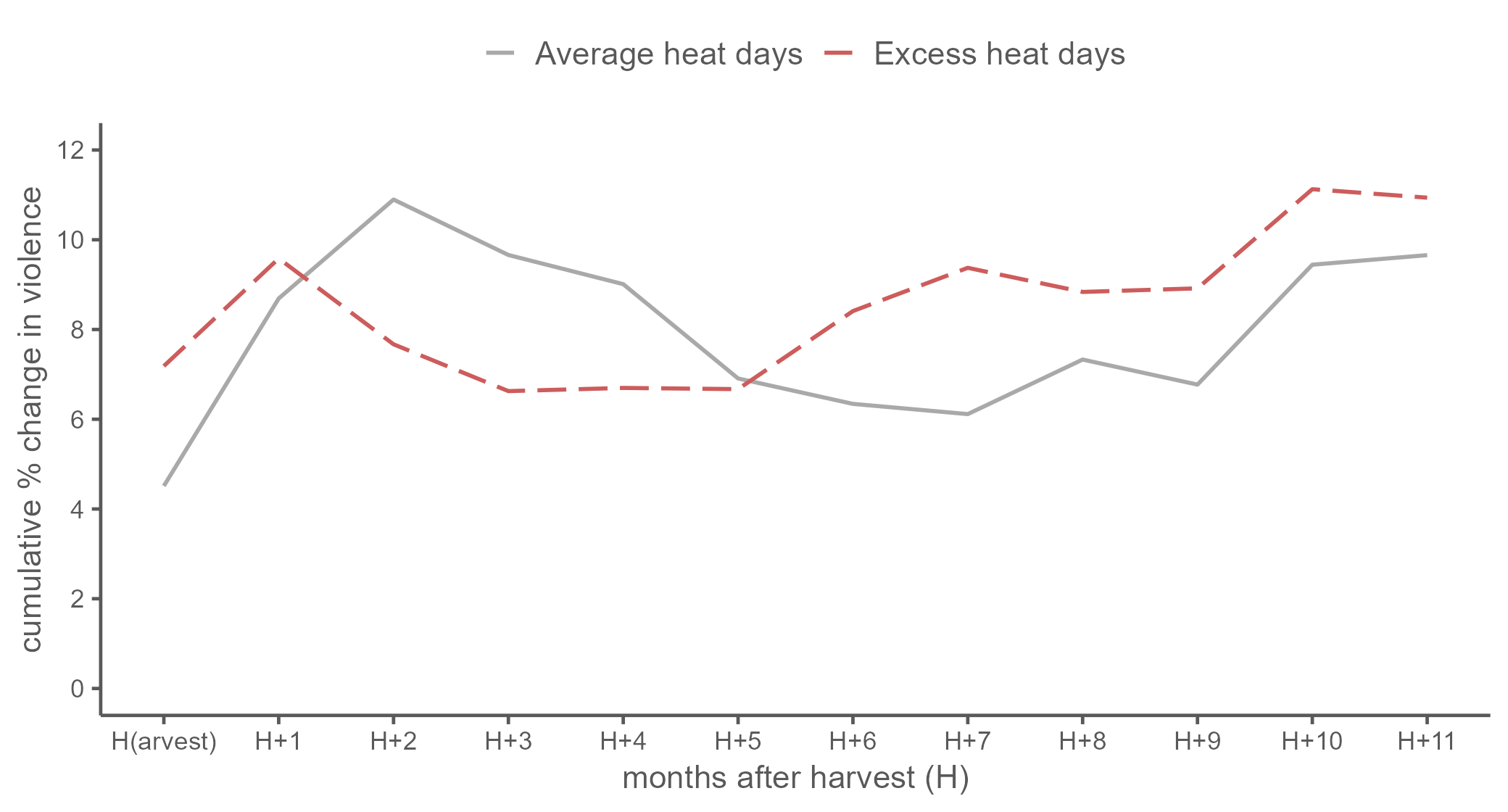

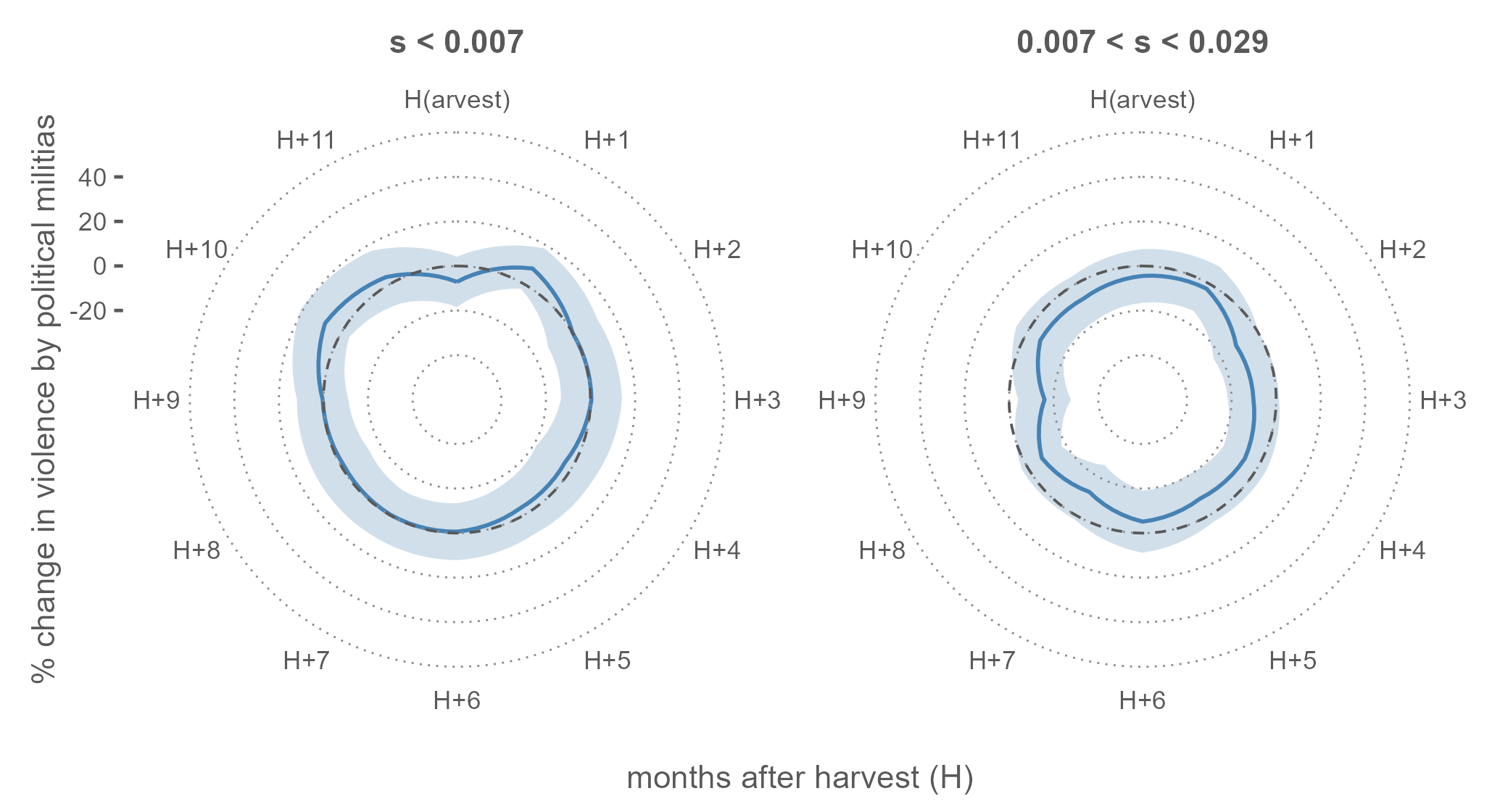

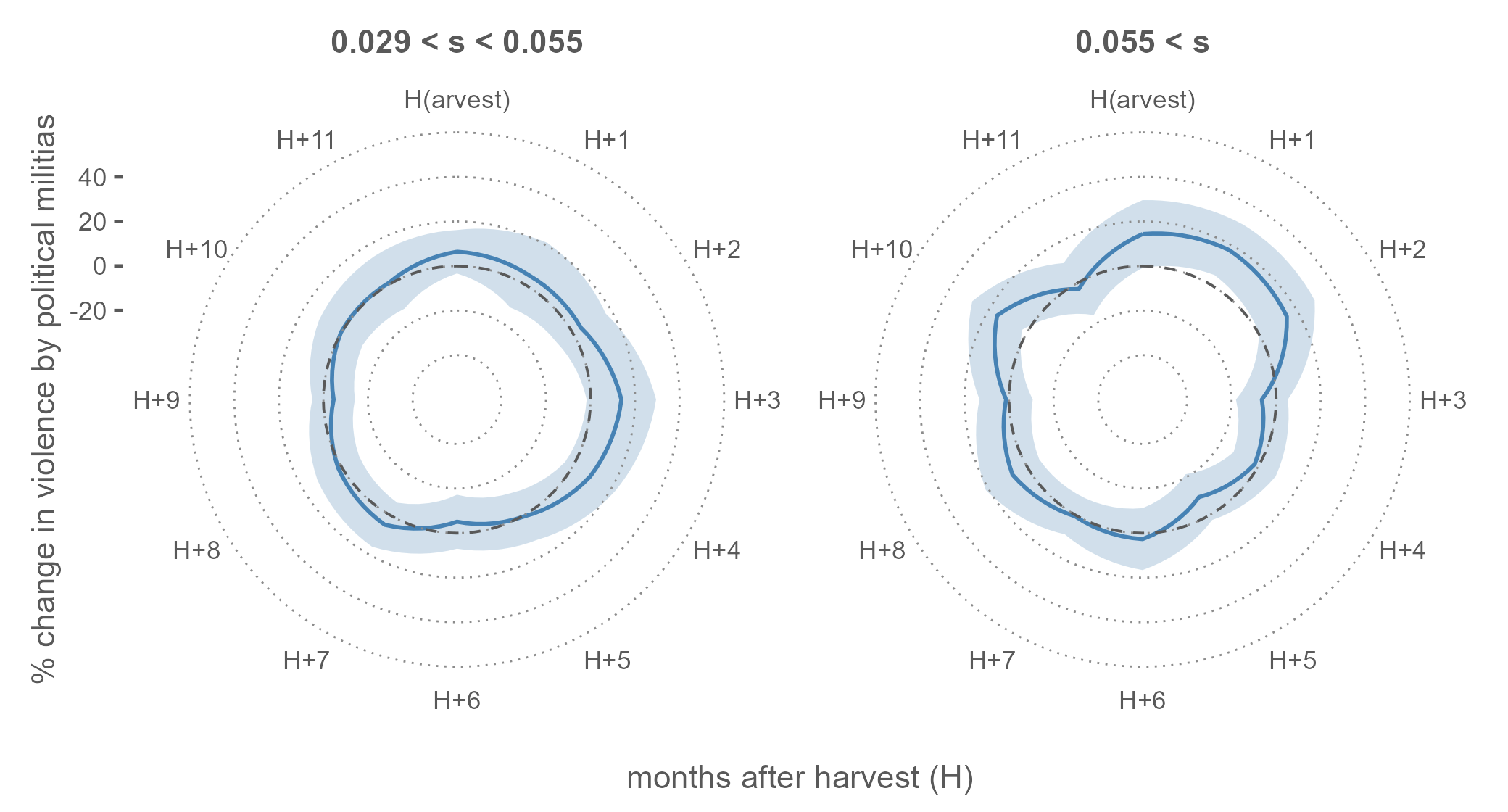

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Agricultural Windfalls and the Seasonality of Political Violence in Africa ## Seminar Presentation ### David Ubilava ### January 2022 --- exclude: true class: inverse, center, middle # Introduction --- # The question - Across (Sub-Saharan) Africa, * more than 60% of population live in rural areas; * more than 50% of total employment is in agriculture; * in some countries (e.g., Niger, Somalia, Uganda), agricultural employment is in excess of 70%. - The inherently seasonal pattern of employment and income can have its footprint on socio-economic outcomes, including on political violence in the region. - So we ask the question: - <span style="color: #4682b4;">**Is there seasonality in violent attacks against civilians across rural Africa?**</span> --- # The answer - A one-standard-deviation price increase of a locally produced cereal crop, results in a monthly 2-4% increase in violence during the harvest and subsequent two months. - The effect is apparent in areas with high cropland fraction. - The effect is larger or more prolonged in the wake of favorable weather conditions during the growing season. - That the increase in violence is associated with agricultural windfalls, points to the seasonal pattern of rapacity and appropriation in agricultural societies. - The key perpetrator is political militias. --- # Some anecdotes - March 2017: a farmer killed as he resisted an attempt to loot his sorghum on his way to market (South Sudan). - July 2016: "Perci" beat a farmer, stole a bag of rice (DRC). - July 2019: Ahlu Sunna Waljama’a attacked farmers harvesting rice, burned plantations, stole food (Mozambique). - September 2017: armed pastoralists killed a farmer, and looted his food (Sudan). --- # The growing literature on the topic <!-- --> - Previous studies have relied on yearly conflict and price data observed at the country level (e.g., [Miguel et al., 2004](https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/421174); [Brückner and Ciccone, 2010](https://academic.oup.com/ej/article/120/544/519/5089581); [Bazzi and Blattman, 2014](https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?%20id=10.1257/mac.6.4.1)), or, more recently, at the grid cell level (e.g., [Fjelde, 2015](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X14003477); [Berman et al., 2017](https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20150774); [Harari and Ferrara, 2018](https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/REST_a_00730)). --- # The growing literature on the topic - [McGuirk and Burke (2020)](https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/709993) argue that data aggregation, typically to the country level, may be an important reason for the ambiguous (or null) results. - They show, using geographically disaggregated grid cell–level data, a positive and statistically significant relationship between cereal crop prices and conflict. --- # Our contribution - We suggest the degree of temporal data aggregation also matters. - The yearly estimates represent the average annual effect and may conceal important seasonal patterns. - We present evidence of the seasonal pattern of violence, plausibly linked with changes in agricultural income due to exogenous price shocks and harvest–related windfalls, in the cropland of Africa. --- # This new finding matters because - it points to a likely temporal displacement of agricultural income–related conflict; - it can facilitate more effective planning by local or international communities toward mitigating conflict or avoiding ambush when operating in conflict–prone regions. --- # Agrarian conflict can be seasonal - because of the intermittent employment in the agricultural sector throughout the marketing year; - due to the abrupt influx of income shortly after harvests. --- # Opportunity cost mechanism - The seasonal employment lends itself to the opportunity cost mechanism of conflict in agricultural sector. - [Guardado and Pennings (2020)](https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-9373) investigate this mechanism of conflict seasonality, and show that in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan, the onset of the harvest reduces conflict. --- # Rapacity mechanism - A harvest–time positive income shock increases farmers’ wealth vs to the rest of the population. - This creates incentives for one group to target the other via robberies and abductions, which lends itself to the rapacity mechanism of conflict (e.g., [Dube and Vargas, 2013](https://academic.oup.com/restud/article-abstract/80/4/1384/1579342), [McGuirk and Burke, 2020](https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/709993)). --- # Rapacity mechanism - Rapacity, in agricultural sector, is likely to be seasonal as looting and appropriation of agricultural surplus are likely to be present most prominently shortly after the harvest, and dissipate gradually as the marketing year progresses. - The higher the value of a crop, the more likely it is that a farmer will engage in a conflict with potential perpetrators. - <span style="color: #4682b4;">**We investigate the rapacity mechanism.**</span> --- # Main data - Conflict data from the ACLED Project ([Raleigh et al., 2010](https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022343310378914)), available at [https://acleddata.com/](https://acleddata.com/). - Price data from the International Monetary Fund's online portal for Primary Commodity Prices, available at [https://www.imf.org/en/Research/commodity-prices](https://www.imf.org/en/Research/commodity-prices). - Crop harvest data from the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment, Nelson Institute at University of Wisconsin-Madison, available at: [https://nelson.wisc.edu/sage/data-and-models/crop-calendar-dataset/index.php](https://nelson.wisc.edu/sage/data-and-models/crop-calendar-dataset/index.php). --- # Auxillary data - Population data from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University available at [https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu](https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu). - Weather data from the ERA5 reanalysis gridded data on daily 2m above the surface air temperatures and monthly averaged total precipitation from European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Copernicus Project, available at [https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels](https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels). --- # Conflict prevalence across Africa <center> <img src="Presentation/incidents_by_country_map.png", width=65%> </center> --- # Perpetrators  --- # Perpetrators  --- # Crop production and prices  --- # Distribution of production intensity  --- # Growing seasons  --- # Harvest seasons  --- # Main specification `$$1(violence_{it,h}) = \sum_{h=0}^{11}\beta_{h}\Delta{p_{it,h}}{s_i}{d_{i,h}} + \mu_i + \lambda_{ct} + \varepsilon_{it,h}$$` - `\(1(violence_{it,h})\)`: incidence of violence `\(h\)` months after harvest in cell `\(i\)` in year `\(t\)`; - `\(\Delta p_{it,h} = p_{it,h}-p_{it-1,h}\)`: seasonally differenced log-transformed price in cell `\(i\)`; - `\(s_i\)`: cropland area fraction; - `\(d_{i,h}\)`: cell-specific crop-year seasonal dummy variables; - `\(\mu_i\)` and `\(\lambda_{ct}\)`: cell and country-year fixed effects. --- # Identifying assumptions - Changes in conflict incidence in cells with no cropland provide a good counterfactual for changes in conflict incidence that would have been observed in cells with cropland had there been no agricultural windfall. - We use international prices, which are unlikely to be affected by conflict in Africa. - We maintain the cropland area fraction and harvest month fixed for each cell to avoid reverse causality in instances when conflict may have caused changes in crop production or harvest timing. --- # Baseline results  --- # Baseline results  --- # Cumulative violence in a crop year  --- # Robustness to omitted latitudes  --- # Robustness to omitted latitudes  --- # Robustness to omitted years  --- # Robustness to omitted years  --- # Robustness to data source  --- # Other robustness checks - Results are robust to different fixed effect specifications * cell, year * cell, year-month * cell, country-trend - Results are robust to different standard error clustering * cell * latitude * Conley (1999) 500km radius --- # Testing mechanisms: precipitation  --- # Testing mechanisms: precipitation  --- # Testing mechanisms: temperature  --- # Testing mechanisms: temperature  --- # Testing mechanisms: dose-response  --- # Testing mechanisms: dose-response  --- # Concluding remarks and takeaways - Seasonality matters. - Commodity price shocks fuel conflict in croplands during the postharvest period, plausibly as a result of increased attempts to appropriate surplus during this period. * The most visible aggressor is *political militias*. - This finding corroborates the recent studies ([Koren, 2018](https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14678276); [McGuirk and Burke, 2020](https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/709993); [McGuirk and Nunn, 2021](https://www.nber.org/papers/w28243)). - We offer more temporally nuanced evidence of the linkage between price (income) shocks and conflict.