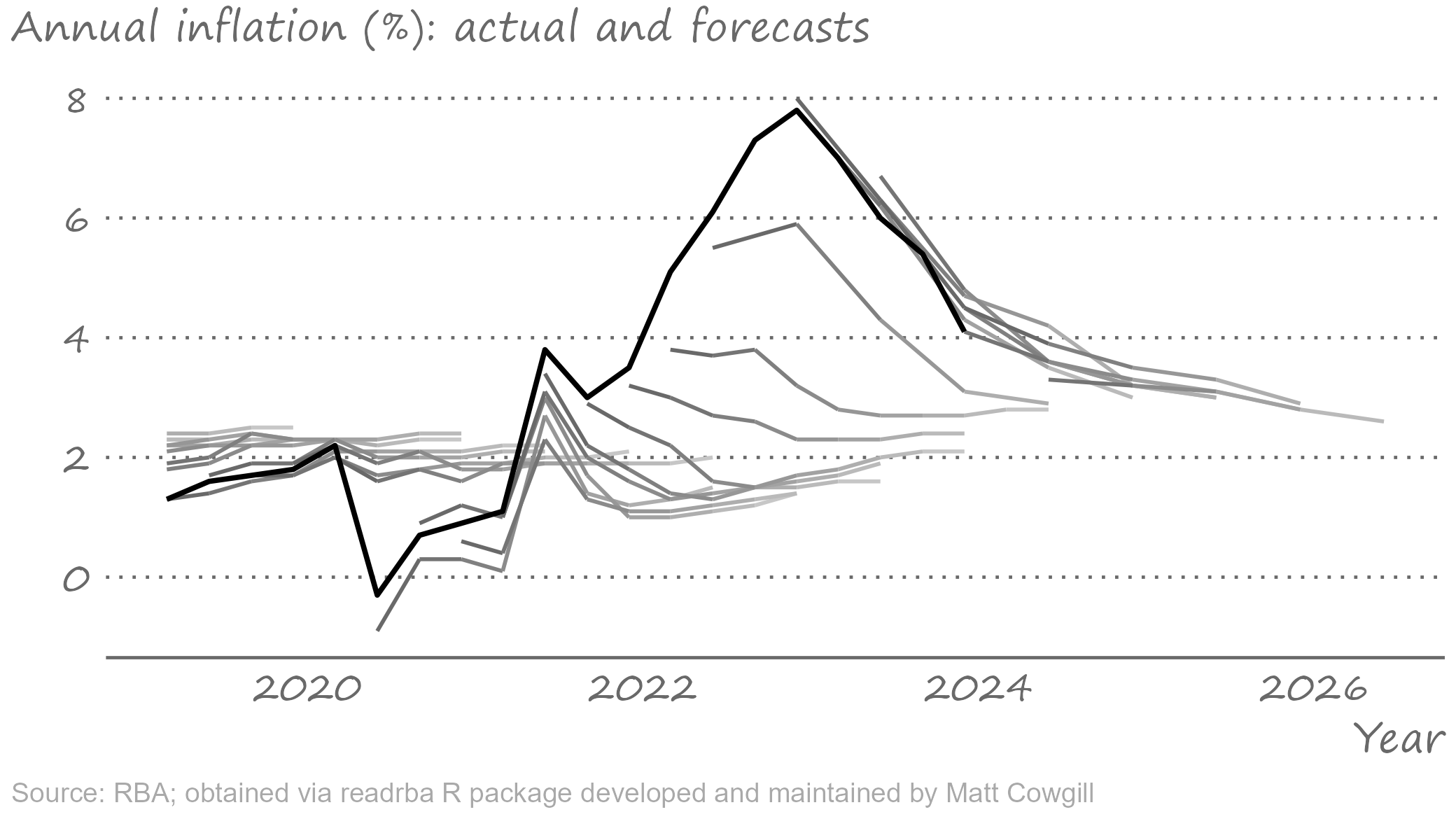

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Forecasting for Economics and Business ] .subtitle[ ## Lecture 1: Introduction to Forecasting ] .author[ ### David Ubilava ] .date[ ### University of Sydney ] --- # People have made forecasts for ages .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The roots of forecasting extend to the early days of human history. In their desire to predict the future, people have attempted to make forecasts of their own, or have used services of others. - Fortunetellers were forecast 'experts' of some sort, basing their predictions on magic. They are less common in the current age. - Astrologers rely on astronomical phenomena to foresee the future. They maintain their relevance to this date. ] --- # Early forecasts mainly revolved around weather .right-column[ We forecast things that matter to us. There are many such things, one of which is weather. Historically, weather was the single most important factor that impacted the livelihood of people, and indeed the fate of civilizations. - The Babylonians based weather forecasts on the appearance of clouds. - The ancient Egyptians measured the levels of the Nile River’s waters to predict an approaching famine due to droughts or destructive floods. ] --- # The tools and techniques improved over time .right-column[ The inventions of the barometer and the thermometer contributed to the development of the study of meteorology. The telegraph made these tools useful - it became possible for the weather forecast to travel sooner than the weather itself. ] --- # Evolution of the economic forecasting .right-column[ The history of economic forecasting does not extend as far into the roots of humankind as does the weather forecasting. - Irving Fisher was one of the first academic economists who contributed to the study of forecasting through his "Equation of Exchange," which he used as the foundation to forecast prices. - Charles Bullock and Warren Persons ran a Harvard-affiliated quasi-academic center for business cycle research with main purpose to generate economic forecasts based on historical precedents. ] --- # Computers and the Internet revolutionised the field .right-column[ The failure to predict the Great Depression adversely impacted the early economic forecasters' reputation and, indeed, fortunes. The evolution of computers in the second half of the 20th century facilitated the resurrection of economic forecasting. Toward the end of the 20th century, the Internet and the ease of storage and distribution of high-frequency granular data further aided the advancement of the study of forecasting. ] --- # What is forecast if not a guess .right-column[ A forecast is a guess about the future event. A guess may be based on one's experience and available knowledge. But, really, it can be any statement about the future, regardless of whether such statement is well founded or lacks any sound basis. We may guess today whether it will rain tomorrow. It may or may not rain tomorrow. With each of these two outcomes having some chance of occurring, our claim about whether it will rain is a guess. ] --- # We guess because we don't know .right-column[ These are events for which several outcomes, each with some chance of appearing, are possible. - We can think of a rain as a discrete random variable (a binary random variable, to be precise): it either rains or it does not rain. By contrast, making a claim about whether the sun will rise tomorrow is hardly a guess. We know with absolute precision when will the sun rise. There is no prophecy about predicting the sunrise. ] --- # A guess is not always a forecast .right-column[ A guess that relies on some knowledge or understanding of the underlying causes of an event is a forecast. - When commercial banks make a guess whether the central bank will increase or decrease the cash rates, they forecast. Otherwise, a guess may as well be a gamble. - Everyone is welcome in a casino so long as gambling is what they do. But when one attempts to "beat the house" using the knowledge accumulated by counting cards, the gamble becomes an educated guess and the gambler becomes *persona non grata*. ] --- # Some events are easier to forecast than others .left-half[ Events that are primarily guided by physical processes or relationships are easier to forecast. - A storm forecast, these days, can be highly accurate. But even then, because what we forecast are random variables, there is always a chance that a potentially good forecast is off the mark. ] .right-half[ [](https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2024-01-22/farmers-frustrated-after-incorrect-bom-el-nino-forecast/103351428?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web) ] --- # Sometimes we cannot forecast because we don't know .right-column[ Much less predictable are events that involve people and their behavioral peculiarities. People, of course, are front and center in business and economic relationships. - Irving Fisher notoriously made the claim in early October 1929 that "*stock prices have reached [...] a permanently high plateau.*" The Wall Street Crash and Great Depression followed shortly after. ] --- # But sometimes - because we know all too well .right-column[ If, through our action, we can influence the future, the information that prompted the action makes the forecast obsolete. Suppose we found out that stock prices of a publicly traded company would increase tomorrow. This creates a temporal arbitrage opportunity. We can buy the stock today when its price is still low, and sell it tomorrow after its price has increased. However, as we (and many other people) act on this information at once, we create demand and drive the prices up today, thus absorbing the temporal arbitrage opportunity. ] --- # Most of the time we don't get it exactly right .right-column[ Sometimes we do, of course, but only by fluke. Our forecast may not be spot-on because: - our idea about how things work (the model) may be far from the truth. - we don't know the parameters of the model, instead we rely on the estimates of the parameters, which can be inaccurate. - we don't know what future holds for us. ] --- # Forecasters are best known for not getting it right .right-column[  ] --- # Information is key in forecasting .right-column[ Forecasters rely (or, at least, they all pretend to rely) on *information*. Information is everything that we know about the event. At any given time, we know what happened in the past but not what will happen in the future. So, information is bounded temporally. We know stuff up to some point in time but not beyond that. Over time we learn more stuff. Simply because what used to be the unobserved future became the observed past. ] --- # Forecasting lends itself to time series analysis .right-column[ When we organize and store the information in a certain way - chronologically and at regular intervals - we obtain a time series of the historical data. Forecasting typically involves analyzing historical time series data to make an informed guess about what is to come in the near or the distant future. The implied assumption is that the past tends to repeat itself. So, if we well study the past, we should be able to predict the future. To the extent that there is no way of getting it exactly right, best we can hope for is that we minimize the risk of getting it wrong. ] --- # The goal is to minimize the risk of getting it wrong .right-column[ Consider a *point forecast*, `\(\hat{y}_{t+h|t}\)`, made in period `\(t\)` for period `\(t+h\)` using available data up to and including `\(t\)`. This a `\(h\)`-step-ahead point forecast. The *optimal* point forecast is the best of all possible point forecasts we can make. One minimizes the risk of getting the forecast wrong. ] --- # The goal is to minimize the risk of getting it wrong .right-column[ We measure risk using a loss function, `\(l(e_{t+h|t})\)`, where `\(e_{t+h|t}=y_{t+h}-\hat{y}_{t+h|t}\)` is the forecast error. The following must hold for the loss function: - `\(l(e_{t+h|t}) = 0\)` for all `\(e_{t+h|t}=0\)` - `\(l(e_{t+h|t}) \ge 0\)` for all `\(e_{t+h|t} \ne 0\)` And (assuming symmetric loss function) for all `\(t \ne s\)`: - `\(l(e_{t+h|t}) \ge l(e_{s+h|s})\)` for all `\(|e_{t+h|t}| \ge |e_{s+h|s}|\)` ] --- # Symmetric loss functions .right-column[ Two commonly used symmetric loss functions are *absolute* and *quadratic* loss functions, respectively given by: `$$\begin{aligned} & l{(e_{t+h|t})} = |e_{t+h|t}| \\ & l{(e_{t+h|t})} = (e_{t+h|t})^2 \end{aligned}$$` The quadratic loss function is popular, partly because it mimics the way we typically estimate the parameters of the model in an 'in-sample' setting (i.e. by minimizing the sum of squared residuals). ] --- # Quadratic loss: graphical illustration .right-column[ <img src="figures/lecture1/loss.png" width="2773" /> ] --- # Loss minimization: graphical animation .right-column[ <!-- --> ] --- # Loss minimization: mathematical derivation .right-column[ Optimal forecast is the forecast that minimizes the expected loss: `$$\min_{\hat{y}_{t+h|t}} \mathbb{E}\left[l\left(e_{t+h|t}\right)\right] = \min_{\hat{y}_{t+h|t}} \mathbb{E}\left[l\left(y_{t+h}-\hat{y}_{t+h|t}\right)\right]$$` Under the assumption of the quadratic loss function: `$$\mathbb{E}\left[l(e_{t+h|t})\right] = \mathbb{E}(y_{t+h}^2)-2\mathbb{E}(y_{t+h})\hat{y}_{t+h|t} + \hat{y}_{t+h|t}^2$$` ] --- # Loss minimization: mathematical derivation .right-column[ By solving the optimization problem it follows that `$$\hat{y}_{t+h|t} = \mathbb{E}(y_{t+h})$$` Thus, under the quadratic loss, and assuming that forecast is normally distributed, the optimal forecast is the mean of the random variable. ] --- # What forecast is and how it can be presented .right-column[ Point forecast is the simplest and (therefore) most popular way to present a forecast. It is a single (the most likely) value of a forecast. Forecast is not one value, however. It's a distribution of possible values. *Density forecast*, `\(f(y_{t+h}|\Omega_t)\)`, where `\(\Omega_t\)` denotes the information set, is the most complete (and somewhat more complex) way to present a forecast. It combines everything that we know or do not know in period `\(t\)` about the event in period `\(t+h\)`. *Interval forecast*, which is the lower and upper percentiles of the forecast distribution, offers a bit more detail than the point forecast but is still not too complex to present or comprehend. ] --- # Key takeaways .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ - We can forecast nearly anything. But not all forecasts are useful. And some forecasts may not even be more accurate than a random guess. - Forecast is a distribution, but we often use a single value, point forecast, as our best guess about the future realization of the event. - Because a forecaster is bound to make an error, there is no such thing as perfect forecast. The goal is to minimize the risk of getting it wrong. ]