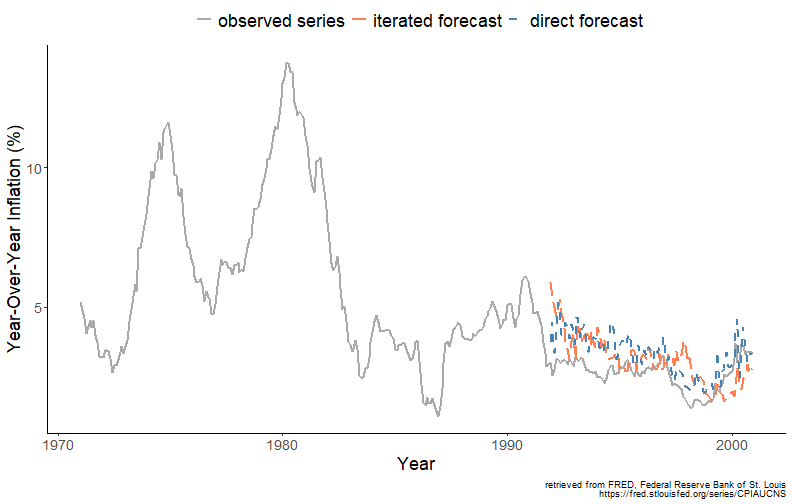

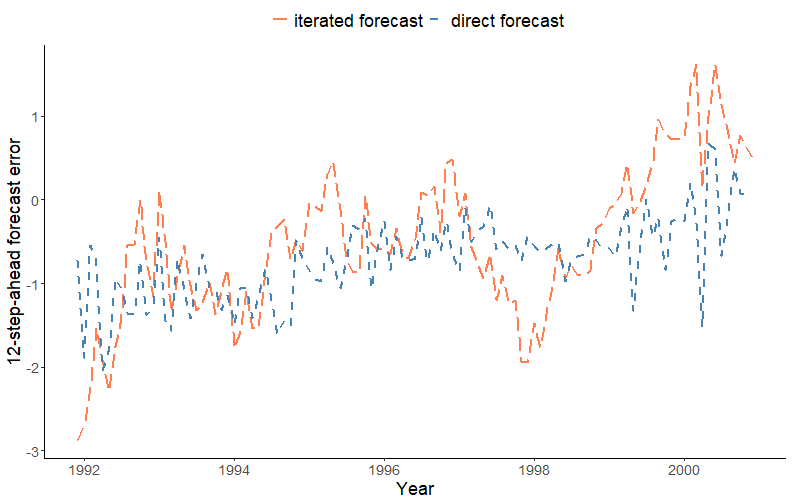

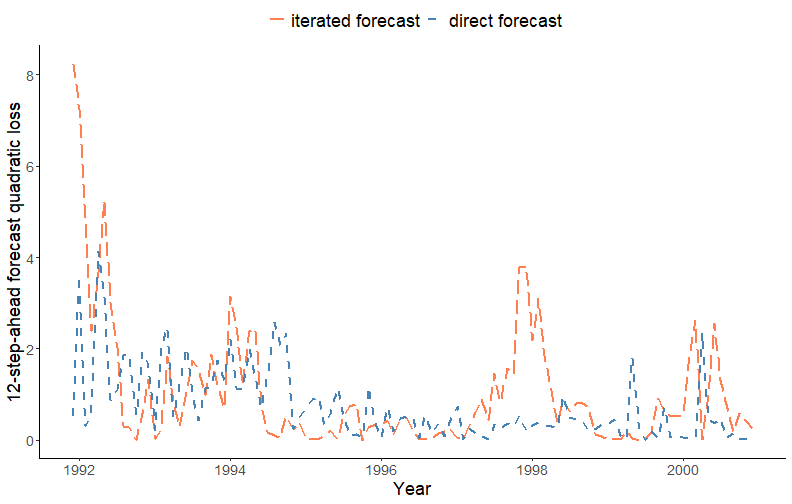

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Forecasting for Economics and Business ] .subtitle[ ## Lecture 9: Testing Relative Forecast Accuracy ] .author[ ### David Ubilava ] .date[ ### University of Sydney ] --- # The Need for the Forecast Evaluation .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ We often have several methods at hand to forecast an economic variable of interest. The challenge, typically, is to identify the best or the most adequate of these models. One way to do so is using in-sample goodness of fit measures (e.g., AIC or SIC). Another more sensible approach, at least from the standpoint of a forecaster, is by evaluating forecasts in out-of-sample setting. ] --- # The Need for the Forecast Evaluation .right-column[ Recall that models with the best in-sample fit don't necessarily produce the best out-of-sample forecasts. While a better in-sample fit can be obtained by incorporating additional parameters in the model, the more complex models can lead to sub-optimal forecasts as they extrapolate the estimated parameter uncertainty into the forecasts. ] --- # Comparing Forecasts .right-column[ Thus far we have applied the following algorithm to identify 'the best' among the competing forecasts: - Decide on a loss function (e.g., quadratic loss). - Obtain forecasts, the forecast errors, and the corresponding sample expected loss (e.g., root mean squared forecast error) for each model in consideration. - Rank the models according to their sample expected loss values. - Select the model with the lowest sample expected loss. ] --- # Comparing Forecasts .right-column[ But the loss function is a function of a random variable, and in practice we deal with sample information, so sampling variation needs to be taken into the account. Statistical methods of evaluation are, therefore, desirable. Here we will cover two tests for the hypothesis that two forecasts are equivalent, in the sense that the associated loss difference is not statistically significantly different from zero. ] --- # Comparing Forecasts .right-column[ Consider a time series of length `\(T\)`. Suppose `\(h\)`-step-ahead forecasts for periods `\(R+h\)` through `\(T\)` have been generated from two competing models `\(i\)` and `\(j\)`: `\(y_{t+h|t,i}\)` and `\(y_{t+h|t,j}\)`, for all `\(t=R,\ldots,T-h\)`, with corresponding forecast errors: `\(e_{t+h,i}\)` and `\(e_{t+h,j}\)`. The null hypothesis of equal predictive ability can be given in terms of the unconditional expectation of the loss difference: `$$H_0: E\left[d(e_{t+h})\right] = 0,$$` where `\(d(e_{t+h,ij}) = e_{t+h,i}^2-e_{t+h,j}^2\)`. ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests ## Morgan-Granger-Newbold Test .right-column[ The Morgan-Granger-Newbold (MGN) test is based on auxiliary variables: `\(u_{1,t+h} = e_{t+h,i}-e_{t+h,j}\)` and `\(u_{2,t+h} = e_{t+h,i}+e_{t+h,j}\)`. It follows that: `$$E(u_1,u_2) = MSFE(i)-MSFE(j).$$` Thus, the hypothesis of interest is equivalent to testing whether the two auxiliary variables are correlated. ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests ## Morgan-Granger-Newbold Test .right-column[ The MGN test statistic is: `$$\frac{r}{\sqrt{(P-1)^{-1}(1-r^2)}}\sim t_{P-1},$$` where `\(t_{P-1}\)` is a Student t distribution with `\(P-1\)` degrees of freedom, `\(P\)` is the number of out-of-sample forecasts, and `$$r=\frac{\sum_{t=R}^{T-h}{u_{1,t+h}u_{2,t+h}}}{\sqrt{\sum_{t=R}^{T-h}{u_{1,t+h}^2}\sum_{t=R}^{T-h}{u_{2,t+h}^2}}}$$` ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests ## Morgan-Granger-Newbold Test .right-column[ The MGN test relies on the assumptions that forecast errors of the forecasts to be compared, are unbiased, normally distributed, and uncorrelated (with each other). These are rather strict requirements that are, often, violated in empirical applications. ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests ## Diebold-Mariano Test .right-column[ The Diebold-Mariano (DM) test relaxes the aforementioned requirements on the forecast errors. The DM test statistic is: `$$\frac{\bar{d}}{\sqrt{\sigma_d^2/P}} \sim N(0,1),$$` where `\(\bar{d}=P^{-1}\sum_{t=1}^{P} d_t\)`, and where `\(d_t \equiv d(e_{t+h,ij})\)`. ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests ## Diebold-Mariano Test .right-column[ A modified version of the DM statistic, due to Harvey, Leybourne, and Newbold (1998), addresses the finite sample properties of the test, so that: `$$\sqrt{\frac{P+1-2h+P^{-1}h(h-1)}{P}}DM\sim t_{P-1},$$` where `\(t_{P-1}\)` is a Student t distribution with `\(P-1\)` degrees of freedom. ] --- # Relative Forecast Accuracy Tests .right-column[ In practice, the test of equal predictive ability can be applied within the framework of a regression model: `$$d(e_{t+h,ij}) = \delta + \upsilon_{t+h} \hspace{.5in} t = R,\ldots,T-h.$$` The null of equal predictive ability is equivalent of testing `\(H_0: \delta = 0\)` in the OLS setting. Because `\(d(e_{t+h,ij})\)` may be serially correlated, an autocorrelation consistent standard errors should be used for inference. ] --- # Direct and Iterated Forecasts of the U.S. Inflation .right-column[ <!-- --> ] --- # Multi-step Forecast Errors .right-column[ <!-- --> ] --- # Forecast Quadratic Loss .right-column[ <!-- --> ] --- # Testing for the Equal Forecast Accuracy .right-column[ We examine the relative out-of-sample performance of the two models by regressing the loss differential `\(d_t=e_{t,d}^2-e_{t,i}^2\)` on a constant, where `\(t=R+h,\ldots,T\)`, and where the subscripts `\(d\)` and `\(i\)` indicate the direct and iterated multistep forecasting method, respectively. In this example, we are unable to reject the null hypothesis of equal forecast accuracy. ``` ## ## t test of coefficients: ## ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) -0.29342 0.24808 -1.1828 0.2395 ``` ] --- # Accuracy Tests for Nested Models .right-column[ When assessing out-of-sample Granger causality, we are comparing nested models. For example, consider a bivariate VAR(1). A test of out-of-sample Granger causality involves comparing forecasts from these two models: `$$\begin{aligned} (A)~~x_{1t} &= \beta_0+\beta_{1}x_{1t-1}+\beta_{2}x_{2t-1}+\upsilon_t \\ (B)~~x_{1t} &= \alpha_0+\alpha_{1}x_{1t-1}+\varepsilon_t \end{aligned}$$` Obviously, here model (B) is nested in model (A). Under the null of Granger non-causality, the disturbances of the two models are identical. This leads to 'issues' in the usual tests. ] --- # Accuracy Tests for Nested Models .right-column[ There is a way to circumvent these issues, which involves an adjustment of the loss differential. In particular, the loss differential now becomes: `$$d(e_{t+h,ij})=e_{t+h,i}^2-e_{t+h,j}^2+(y_{t+h|t,i}-y_{t+h|t,j})^2,$$` where model `\(i\)` is nested in model `\(j\)`. ] --- # Does interest rate Granger cause inflation rate? .right-column[ We examine the out-of-sample performance of the AR(p) model relative to that of the equation from the VAR(p) model by regressing the adjusted loss differential `\(d_t=e_{t,r}^2-e_{t,u}^2+(y_{t|t-1,r}^2-y_{t|t-1,u}^2)^2\)` on a constant, where `\(t=R+h,\ldots,T\)`, and where the subscripts `\(r\)` and `\(u\)` indicate the restricted and unrestricted models, respectively. Here, we are unable to reject the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality. ``` ## ## t test of coefficients: ## ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 0.00104507 0.00069574 1.5021 0.136 ``` ] --- # Readings .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Ubilava, [Chapter 9](https://davidubilava.com/forecasting/docs/forecast-evaluation.html) Gonzalez-Rivera, Chapter 9 ]