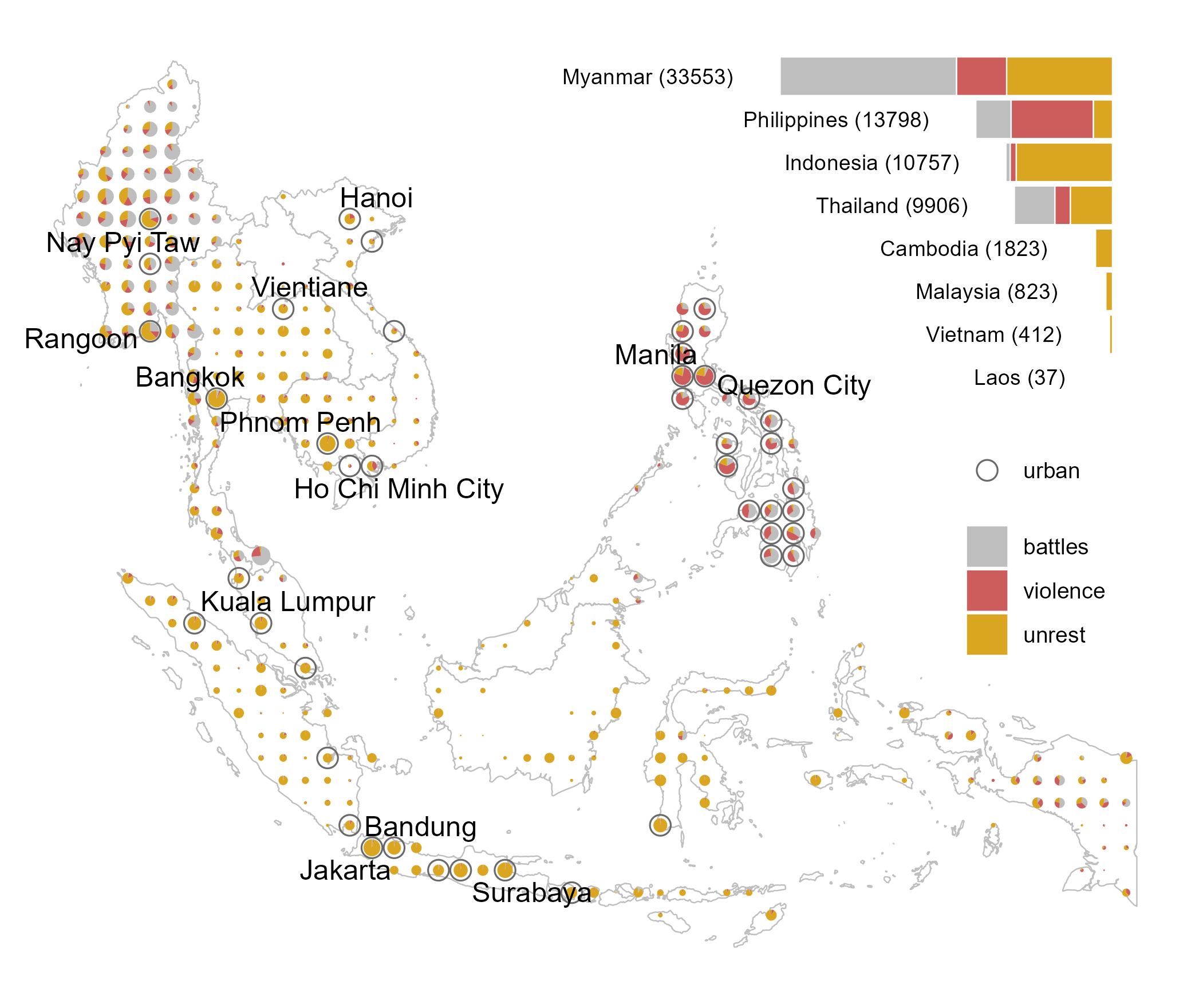

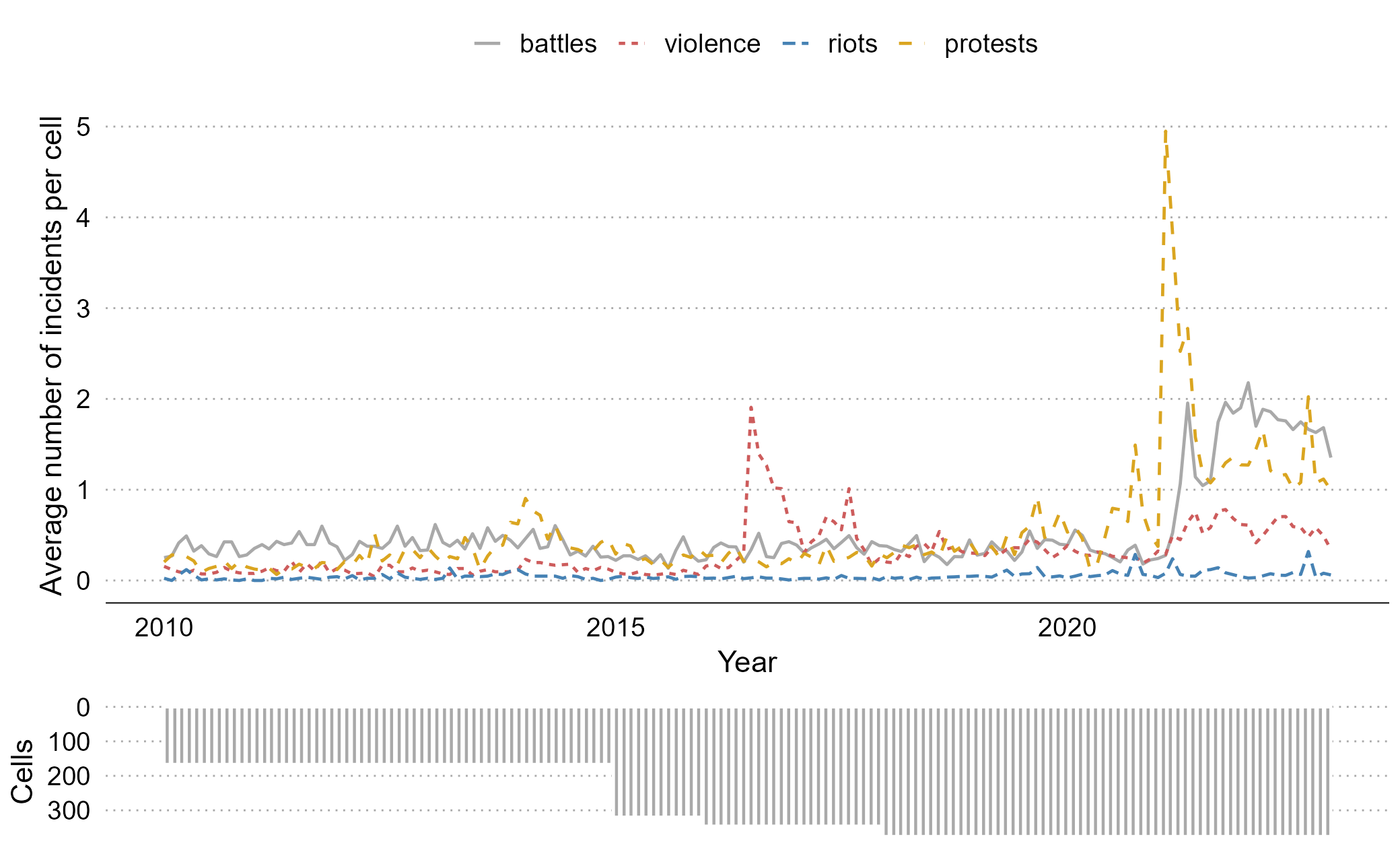

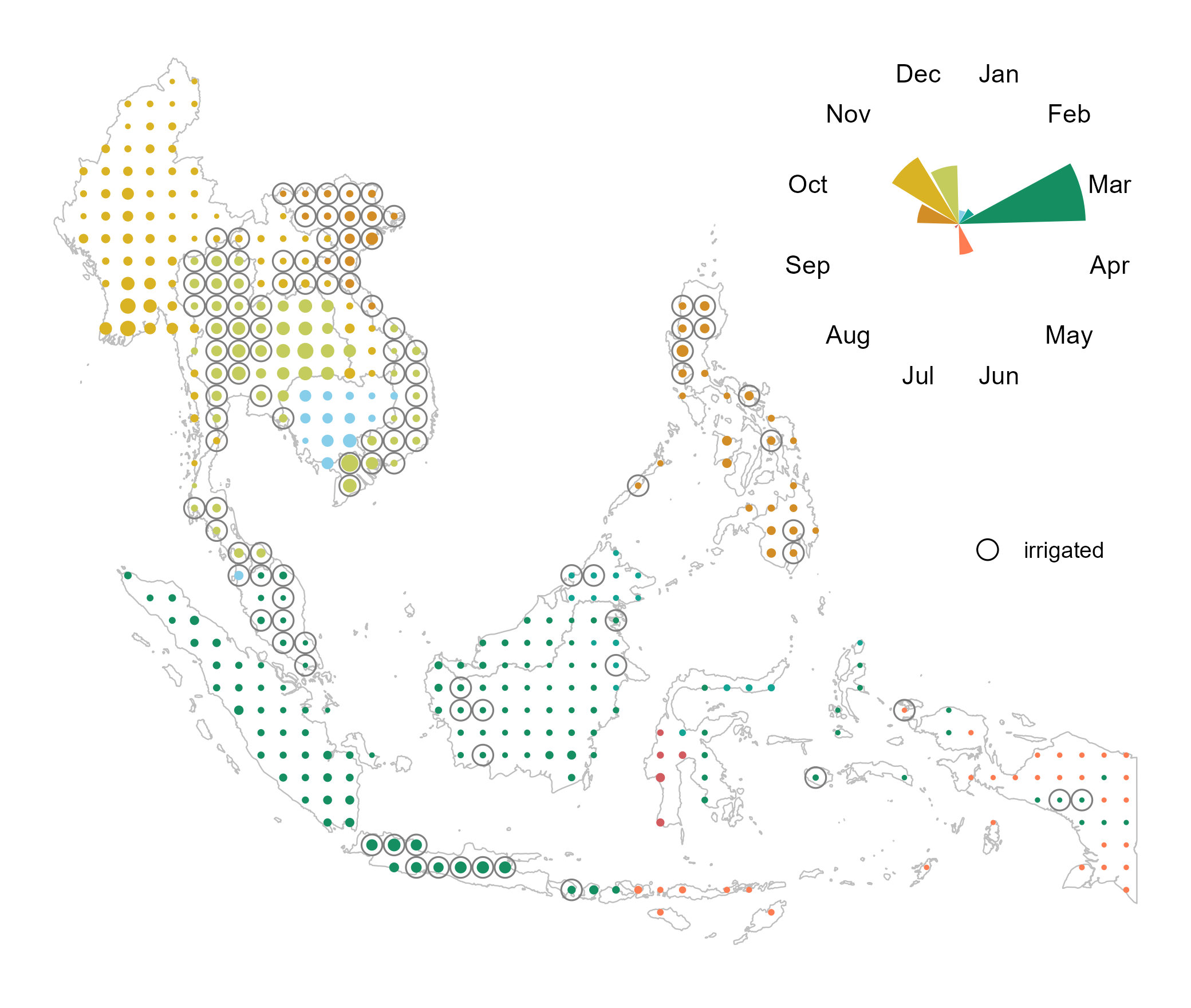

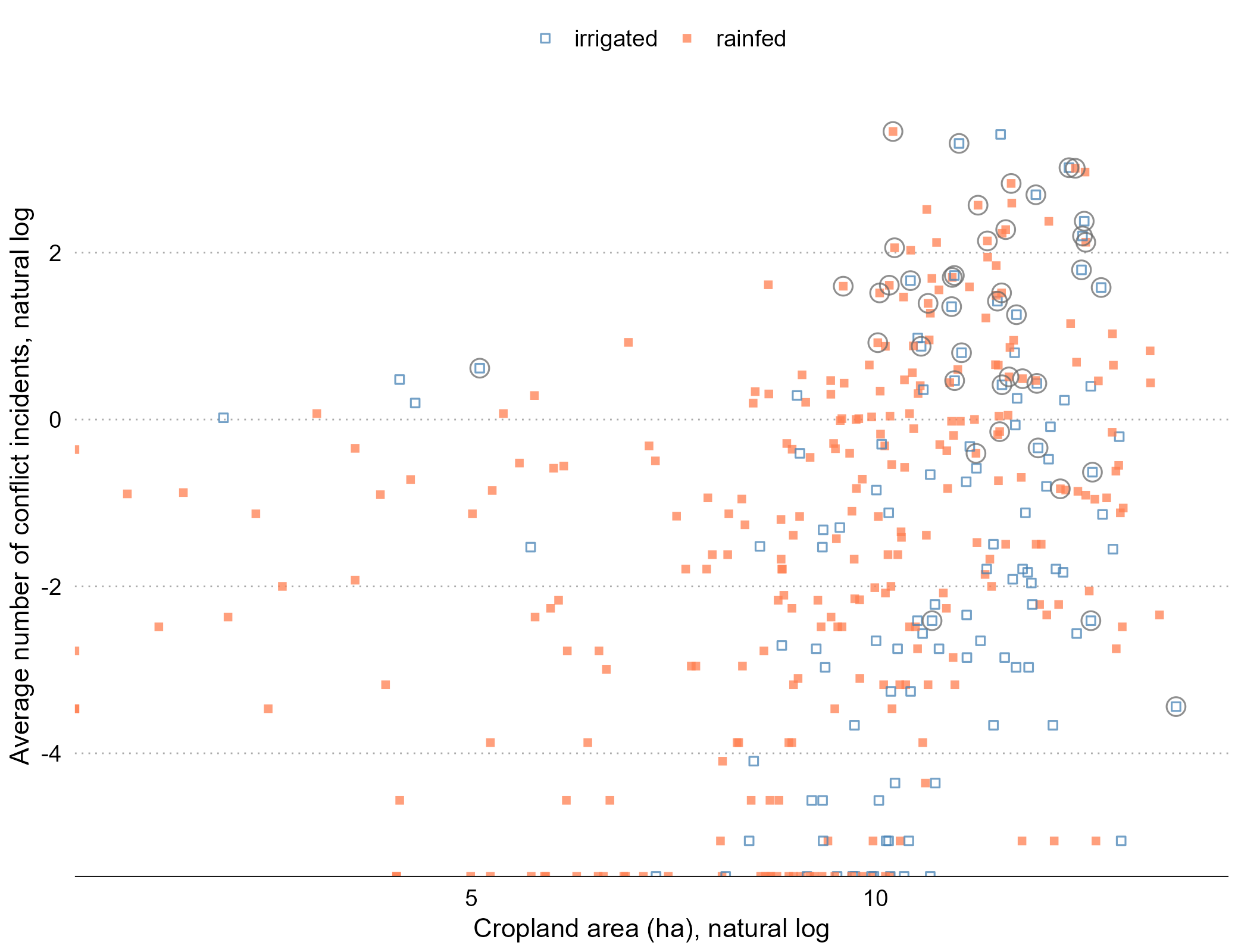

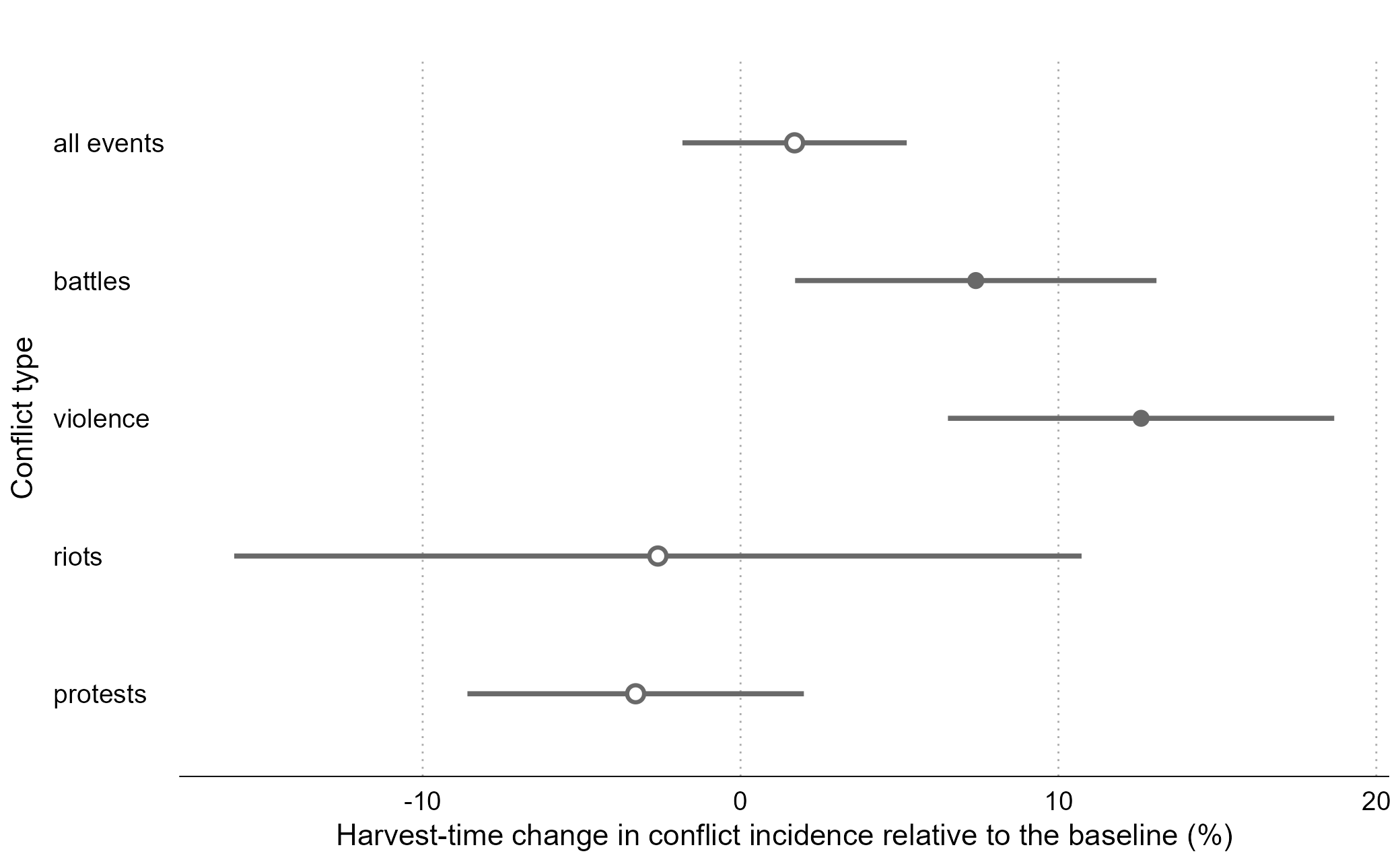

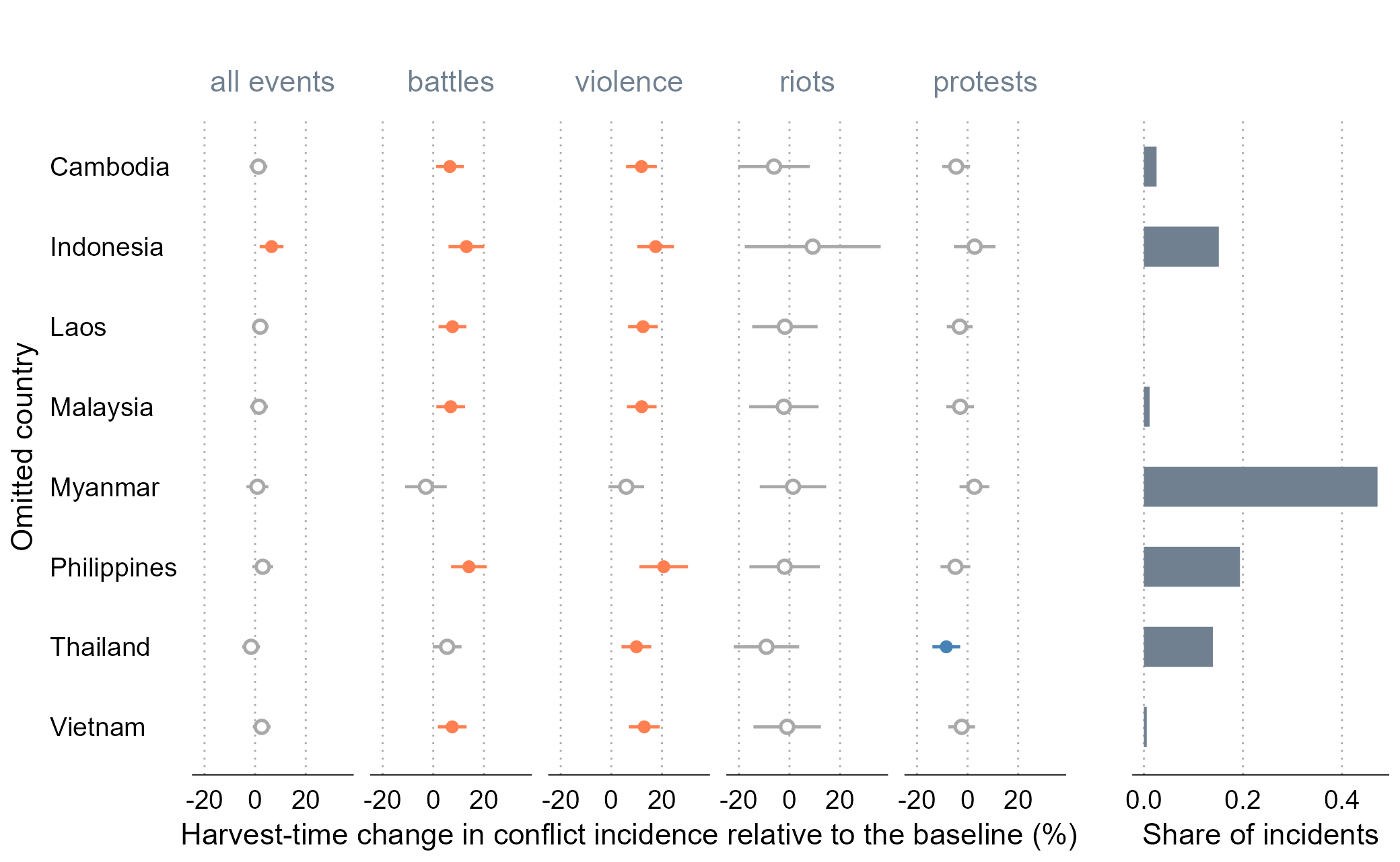

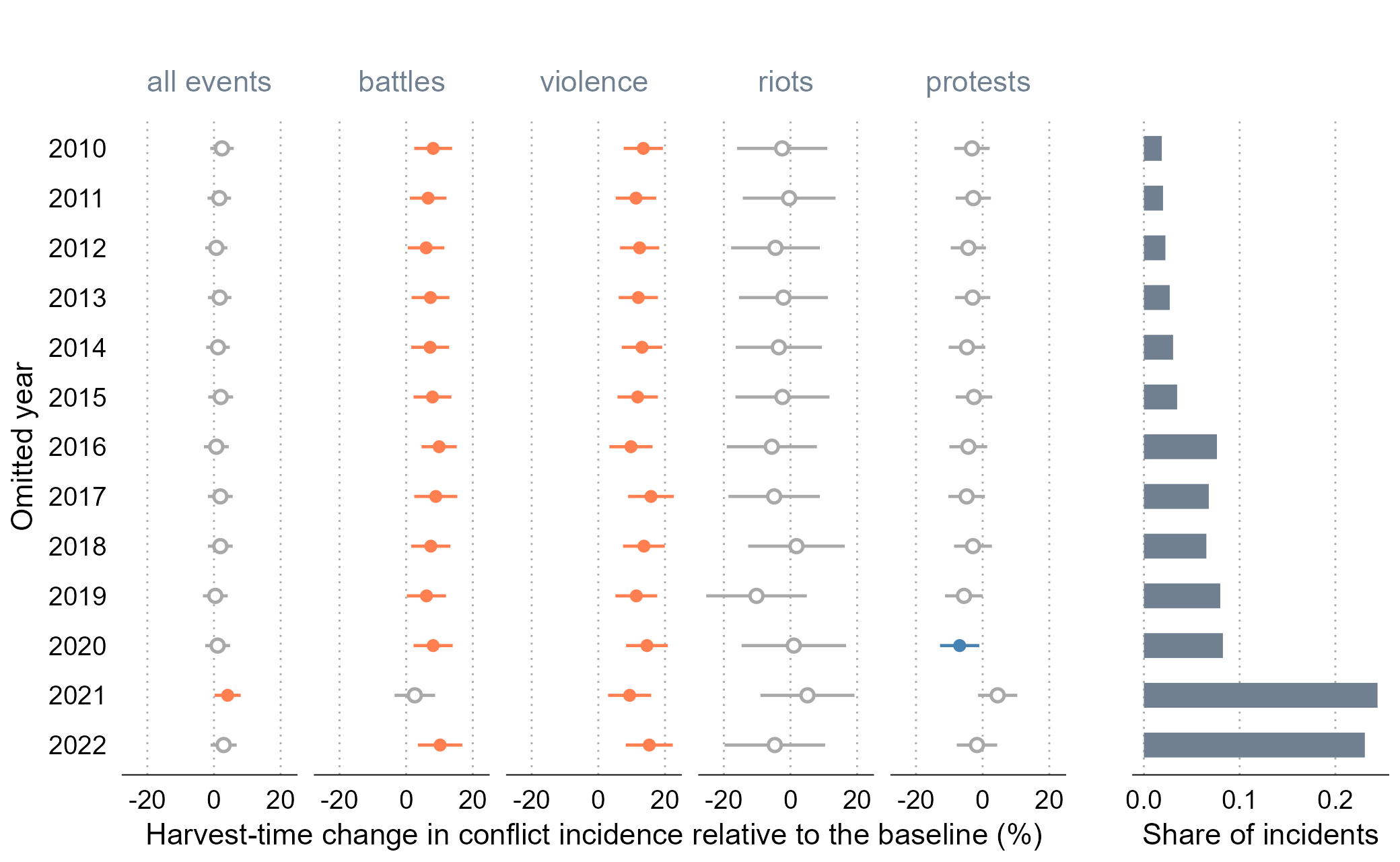

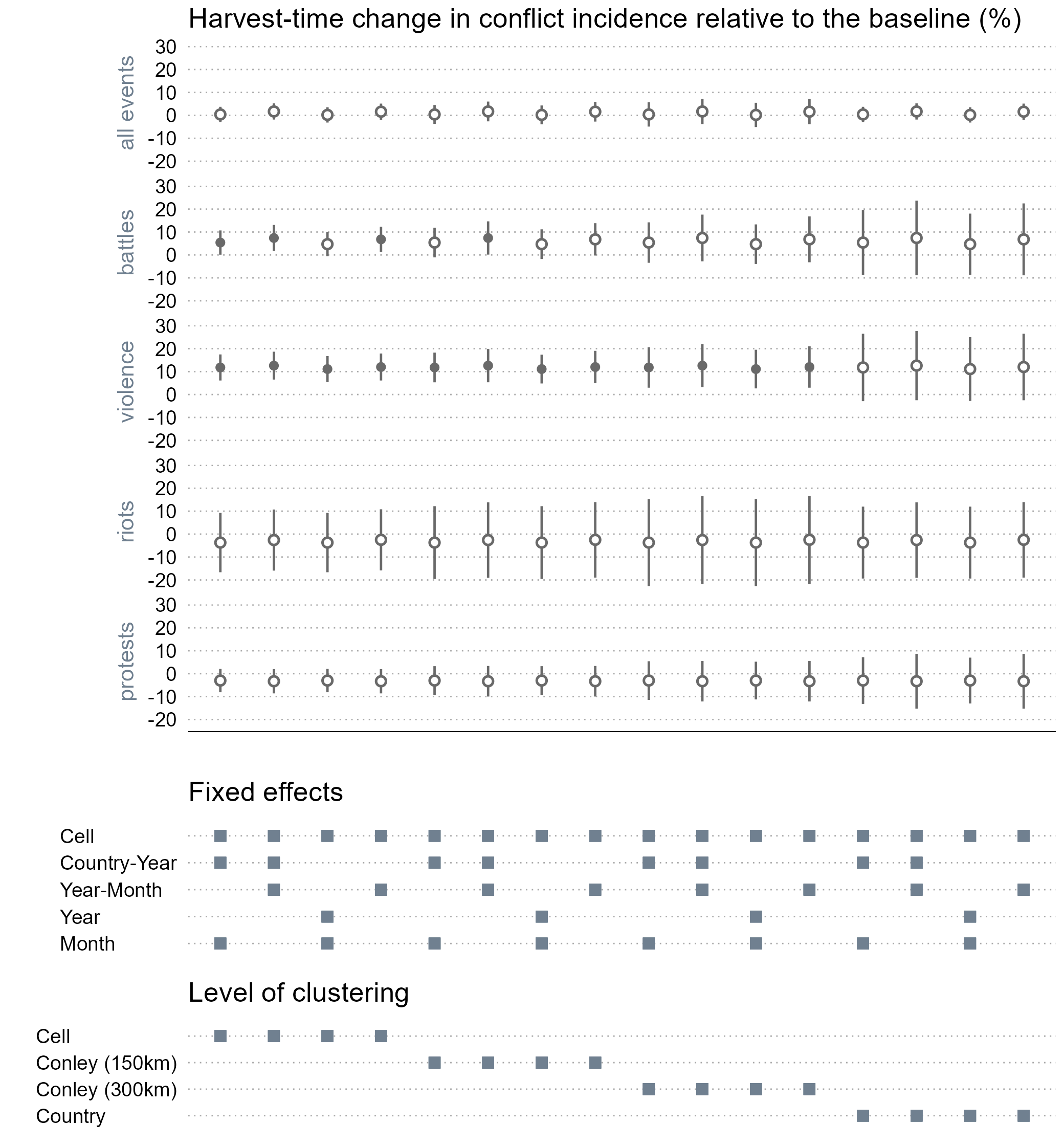

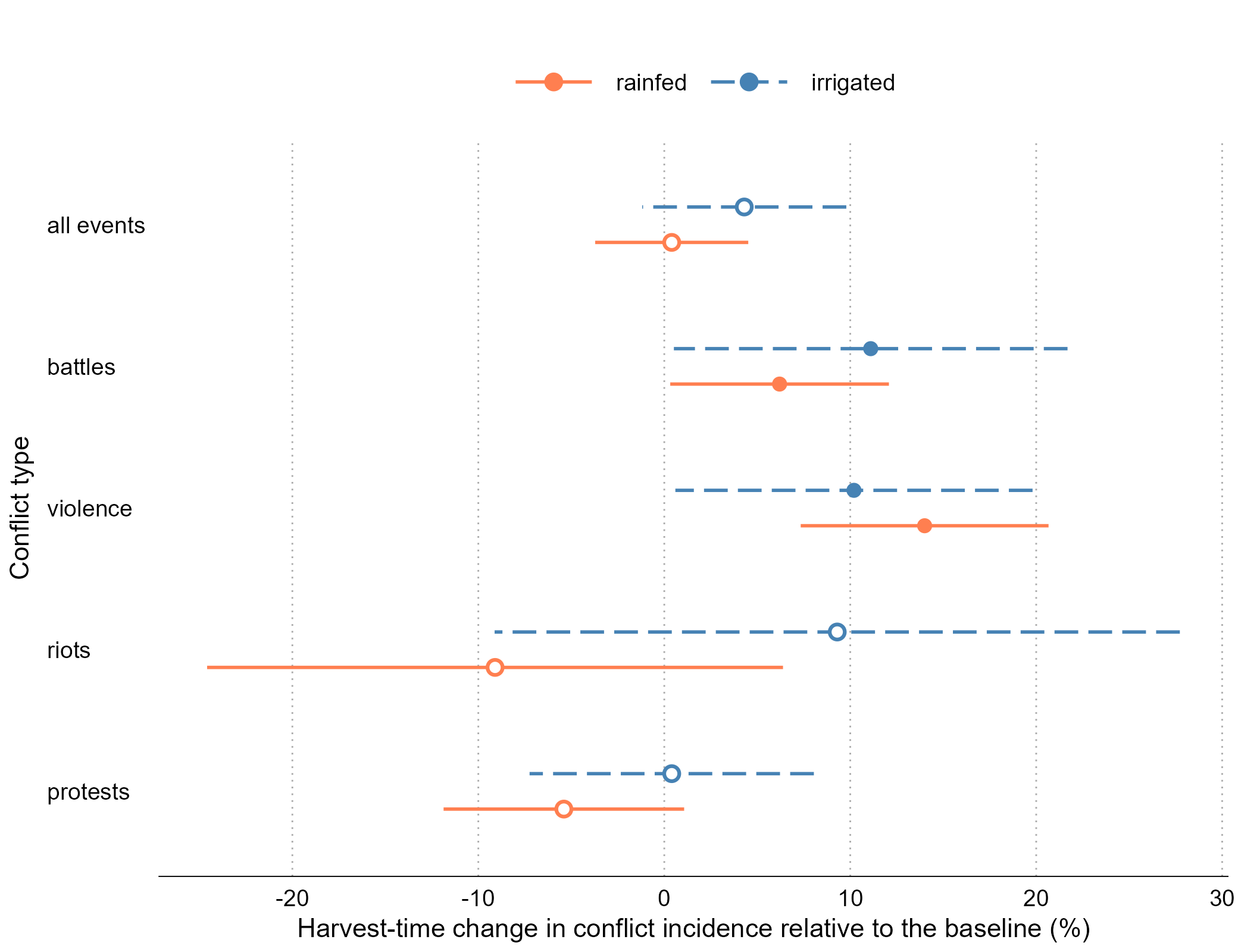

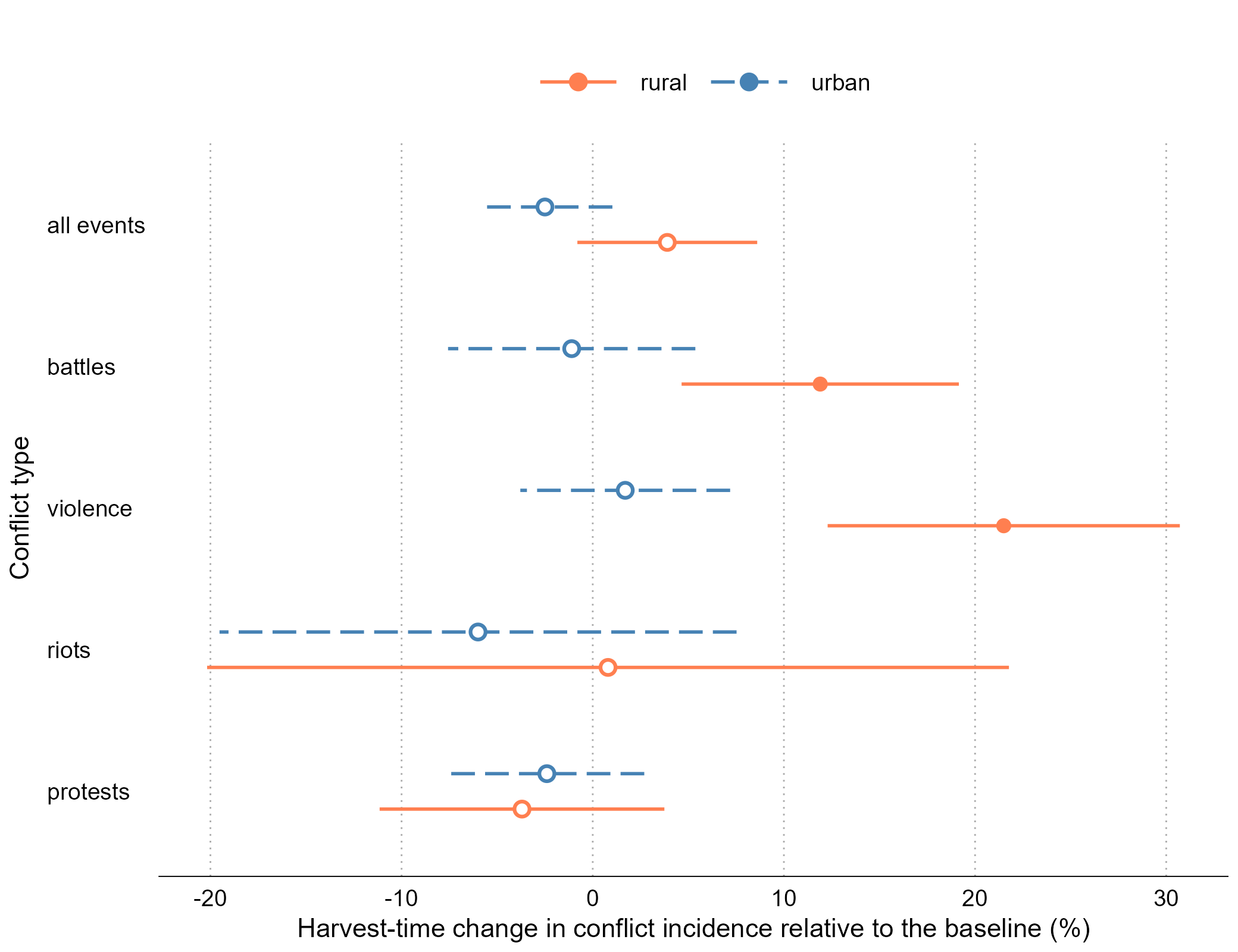

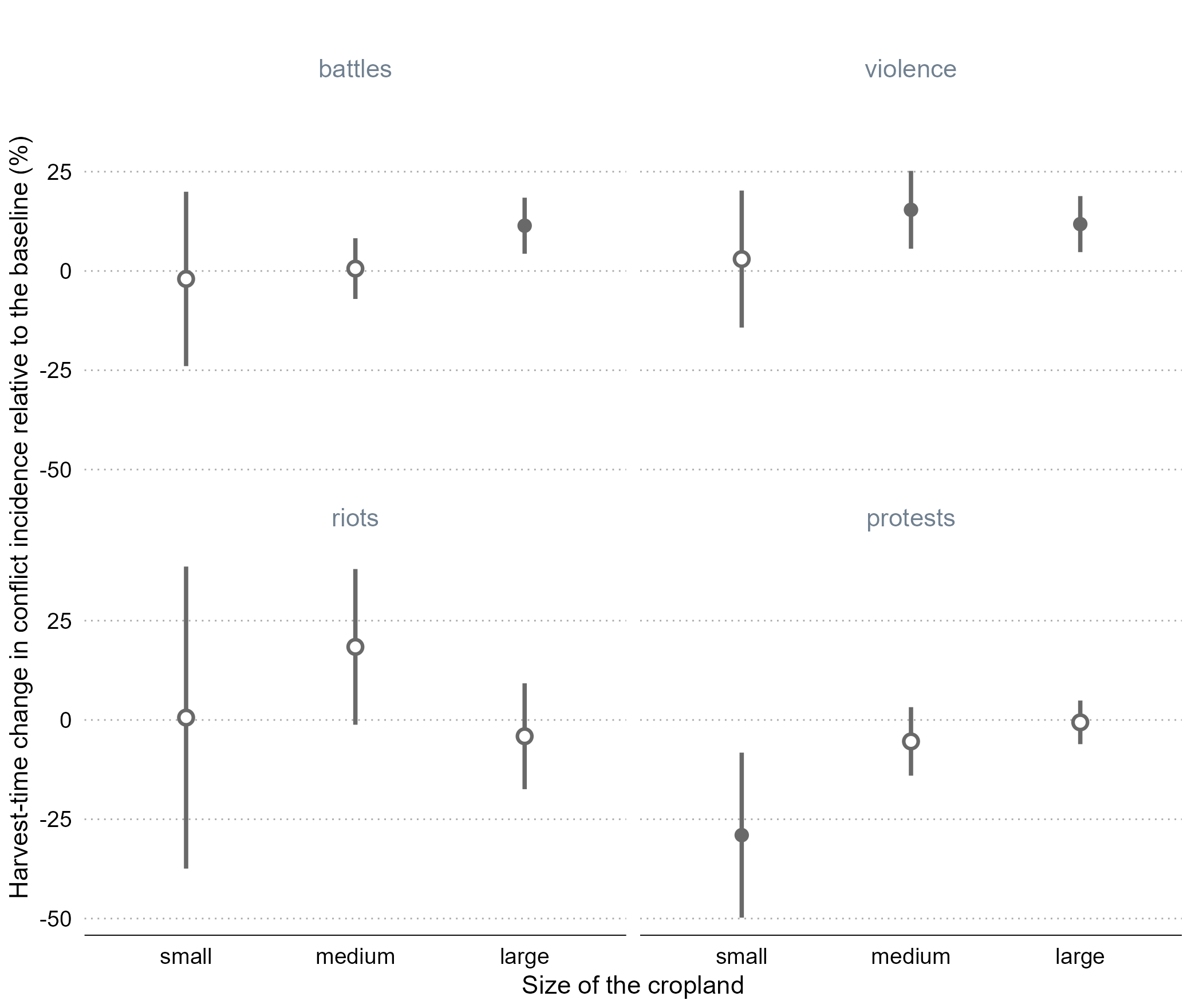

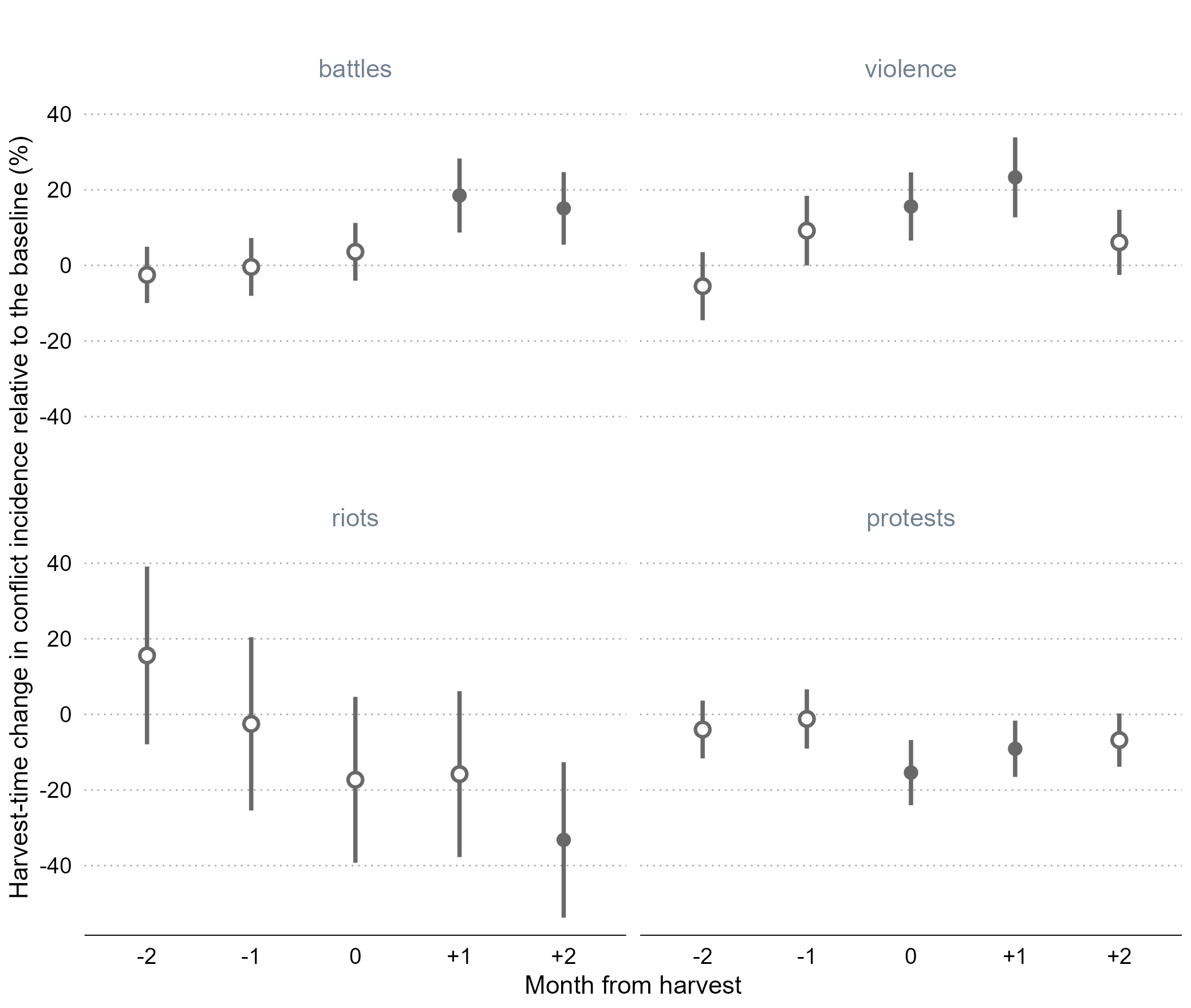

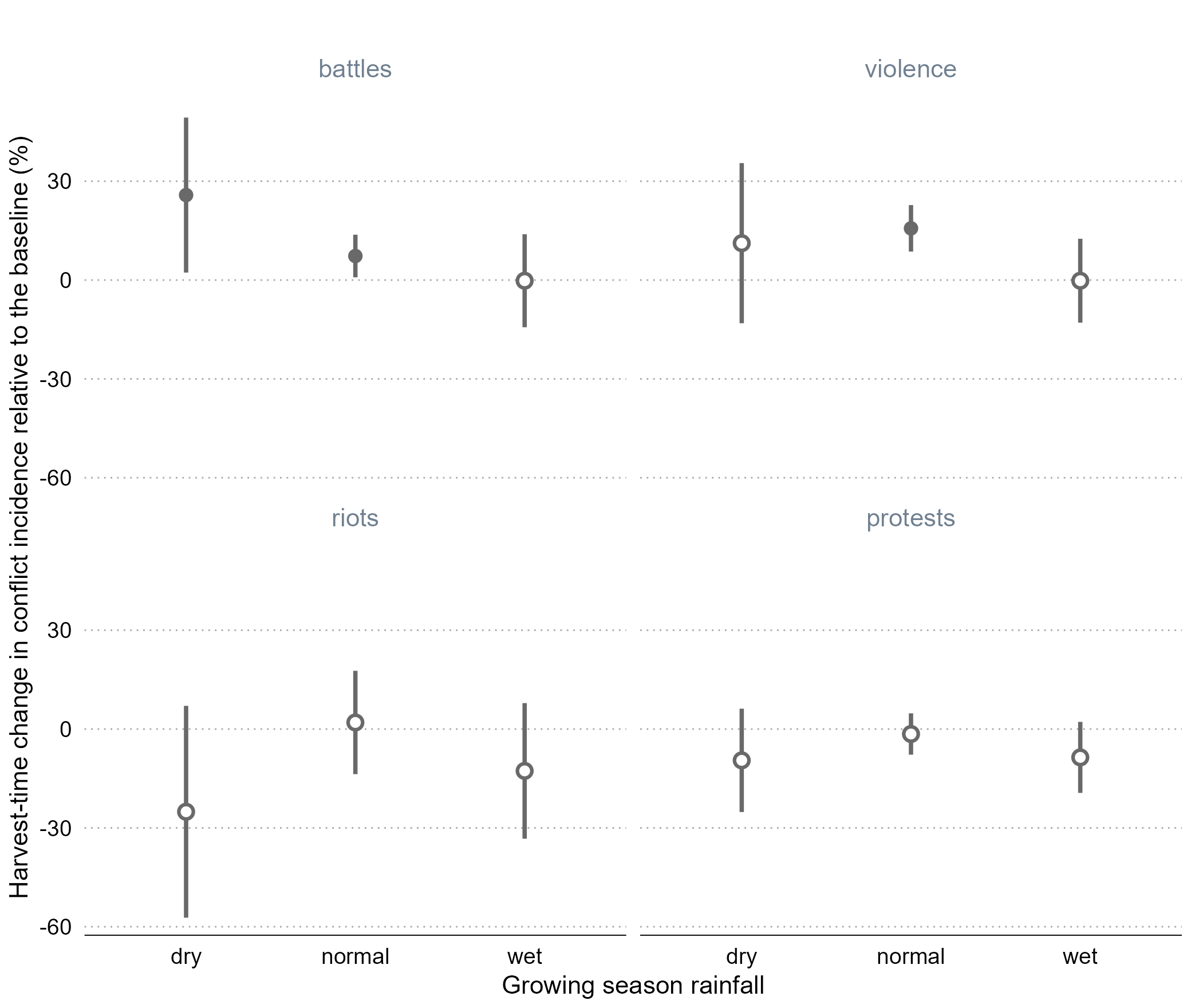

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Agricultural Shocks and Social Conflict in Southeast Asia ] .author[ ### David Ubilava ] .date[ ### University of Sydney ] --- # Agriculture and conflict are linked; sometimes literally .right-90[  ] --- # But, more typically, possibly also causally .right-90[ We focus on low- and middle-income countries of Southeast Asia, where agriculture employs and pays large shares of population. We ask the question: > Do harvest-time agricultural shocks lead to changes in forms of conflict? ] --- # Harvest-time violence may be linked to rapacity .right-90[ [Ubilava et al. (2023)](https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12364) investigate the effect of cereal price change on seasonal violence in the croplands of Africa. The key finding: much of the annually accrued effect—which is positive, statistically significant, and economically meaningful—happens during the first three months of the crop year. Accords with the *rapacity mechanism*: farmers attacked when most gains are to be made (or maximum damage incurred). ] --- # Opportunity cost may explain less protests .right-90[ The *opportunity cost mechanism* often is portrayed as a trade-off a person faces between farming and fighting. Agricultural shocks may push a person in one direction or another... but this is a longer term engagement. In the short run, the opportunity cost mechanism is well-suited to explain the lack of protests at harvest time. But, some of this may be offset by *resentment*, i.e., when people feel being worse off only because others are doing well. ] --- # More violence and (maybe) less protests at harvest .right-90[ Relative to the rest of the year, at harvest time we estimate: - more than ten percent increase in violence against civilians - up to ten percent increase in battles* - up to ten percent decrease in protests* `$$\\[.5in]$$` *sensitive to data subsetting or changes in model specification. ] --- # Conflicts happen all across Southeast Asia .left-50[ From the [ACLED Project](https://acleddata.com/), over 70 thousand incidents of: - <span style="color:dimgray">**battles**</span>, - <span style="color:dimgray">**explosions/remote violence**</span>, - <span style="color:indianred">**violence against civilians**</span>, - <span style="color:goldenrod">**riots**</span>, and - <span style="color:goldenrod">**protests**</span> observed over the 2010-2022 period. ] .right-50[  ] --- # Conflicts happen all the time in Southeast Asia .left-40[ Unbalanced panel of eight countries. For most countries, the data are available from 2010 onward, except for: - Indonesia (2015-) - Philippines (2016-) - Malaysia (2018-) ] .right-60[  ] --- # Rice is cultivated across all of Southeast Asia .left-50[ From IFPRI's [Spatial Production Allocation Model](https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/PRFF8V) (SPAM) and [Sacks et al. (2010)](https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00551.x), - regional variation in the sizes of harvested area - regional variation in the timing of harvest seasons - regional variation in the proportions of irrigated land ] .right-50[  ] --- # Positive correlation between conflict and croplands .left-40[ Generally positive relationship between the size of croplands and the average number of incidents in the cell Seemingly negative relationship between these two variables in 'urban' cells ] .right-60[  ] --- # The effect of harvest on the incidence of conflict .right-90[ The outcome variable is the incidence of conflict in a given cell at a given period (year-month). We consider: - all forms of conflict combined, and - each form of conflict separately. The treatment variable is the product of the cropland indicator (harvest area `\(\ge\)` 10,000ha) and harvest season indicator. Fixed effects: cell, country-year, year-month. ] --- # Battles and violence increase and protests decrease .left-40[ The estimated effect is evaluated at the average size of the cropland and relative to the average conflict. The dots are point estimates, and errorbars denote 95% confidence interval. ] .right-60[  ] --- # Myanmar is driving the results .left-40[ This comes hardly as a surprise, since nearly half of the observations come from Myanmar. ] .right-60[  ] --- # 2020 and 2021 are driving (some of) the results .left-40[ Likely linked with pandemic-related restrictions in 2020, and the onset of the Myanmar conflict in 2021. ] .right-60[  ] --- # The specification chart .left-40[  ] .right-60[ The effect on violence robust across most specifications. ] --- # Heterogeneity: rainfed vs irrigated .left-40[ The harvest-time increase in violence and (statistically insignificant) decrease in protests more prominent in rainfed locations. ] .right-60[  ] --- # Heterogeneity: rural vs urban .left-40[ The harvest-time increase in battles and violence is a rural phenomenon. ] .right-60[  ] --- # Mechanisms: harvest intensity .left-50[ The harvest-time increase in battles and violence is more prominent in larger croplands. The harvest-time decrease in protests observed in small croplands only. ] .right-50[  ] --- # Mechanisms: harvest timing .left-50[ The harvest-time increase in battles lingers post-harvest (possibly picking up the dry-season effect). The harvest-time increase in violence and decrease in protests are centered on the harvest month. ] .right-50[  ] --- # Mechanisms: harvest quality .left-50[ The harvest-time increase in battles negatively correlated with the growing season rainfall. The harvest-time decrease in violence, as well as protests and riots, have inverted V-shaped patterns relative to the growing season rainfall. ] .right-50[  ] --- # We contribute to three strands of conflict literature .right-90[ Climate and conflict ([Burke et al., 2009](https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.0907998106); [Hsiang et al., 2013](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1235367); [Crost et al., 2018](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095069617301584)) Income and conflict ([Berman et al, 2011](https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022002710393920); [Crost and Felter, 2020](https://academic.oup.com/jeea/article/18/3/1484/5505371); [McGuirk and Burke, 2020](https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/709993)) Seasonality of conflict ([Harari and La Ferrara, 2018](https://direct.mit.edu/rest/article-abstract/100/4/594/58501/Conflict-Climate-and-Cells-A-Disaggregated); McGuirk and Nunn, 2023; Guardado and Pennings, 2023; [Ubilava et al., 2023](https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12364)) ]