Chapter 6 Environmental Regulation

Kolstad (2010, Chapters 11 & 12); Keohane and Olmstead (2016, Chapter 8); Keohane (2009)

Any given problem associated with a market failure can have multiple solutions, which are manifested through regulations of some sort. The challenge, often, is to identify the best of those solutions, i.e., the most effective regulation.

6.1 Rationale for Regulation

Environmental (or, more broadly, economic) regulation involves the government intervening in the private actions of firms and individuals. Two basic theories of regulation are the public interest theory, and the interest group theory.

The public interest theory of regulation is a normative theory. It views the purpose of regulation as the promotion of public interest. Three general reasons for the regulation to exist: imperfect competition, imperfect information, and externalities.

- Imperfect competition: the role of government is to control prices in order to protect consumers from monopoly pricing, and in some instances—i.e., in the case of natural monopoly—to restrict the entry of new firms.

- Imperfect information: the role of government is to establish a set of liability rules to facilitate, say, the provision of quality (passive or indirect intervention), or to specify acceptable levels of quality (active or direct intervention).

- Externalities: the usual approach for government is to define a set of institutions and regulations to govern the provision of public bads and negative externalities.

The interest group theory of regulation is a positive theory. It views the purpose of regulation as the promotion of the narrow interests of particular groups in society, and maintains that rent seeking is the primary rationale for regulation. Rent Seeking involves private individuals or firms using the government to guarantee extra benefits (rents) through government-mandated restriction on economic activity.

Most environmental regulations fall into two broad categories: prescriptive regulations (also referred as command-and-control) and incentive-based regulations.

6.2 Prescriptive Regulation

Command-and-control is the dominant form of environmental regulation in the world. Its fundamental principle is for the regulator to specify the steps individuals or firms must take to mitigate/solve the environmental problem.

There are two basic types of prescriptive regulations: technology standards and performance standards.

- Technology standards typically specify a particular type of equipment that must be used.

- Performance standards typically stipulate the maximum emissions allowed per unit of economic activity. This is a more flexible method of regulation, which typically leads to improved cost-effectiveness (at least compared to that of a technology standard).

Often, a regulation combines performance standards with technology standards. Prescriptive regulations may, in fact, be present in conjunction with fines and penalties associated with noncompliance; these are different from—and should not be confused with—economic incentives to abate pollution.

Two key features that distinguish prescriptive regulations from incentives are:

- restricted choice for the polluter as to what means to be used to achieve an appropriate environmental target, and

- a lack of mechanisms for equalizing marginal costs of managing emission among several different polluters.

The advantage of prescriptive regulations is in greater certainty in the pollution levels, as well as in simplifying monitoring of compliance with a regulation.

The disadvantages to prescriptive regulations are:

- cost (costliness) of administering the regulation;

- reduced incentives (for a firm) to find better ways to control pollution;

- not accounting for residual damage from the pollution that is still emitted after controls are in place;

- difficulty in satisfying the equimarginal principle.

For the equimarginal principle to hold, in controlling emissions from several polluters, marginal cost of emission control must be the same for all polluters.

6.3 Incentive–Based Regulation

Economic incentives, in contrast to prescriptive regulations, provide rewards to potential polluters to do what is perceived to be in public interest.

Three basic types of economic incentives are: marketable permits, emission fees, and liability.

Emission fees involve the payment of a charge per unit of pollution emitted. It then becomes in a polluter’s interest to reduce emissions.

Marketable permits allow polluters to buy and sell the right to pollute. By enabling the trade of permits, something of similar character to a prescriptive regulation (a permit to pollute) becomes an economic incentive. The marketable permit system is often referred as cap–and–trade, wherein the regulator sets a cap on overall emissions, and allows trading among polluters to determine who emits what. Trading induces a price or value on a permit to pollute.

Liability is based on a simple concept: if you incur a damage, you must compensate for the damage. Importantly, the regulator does not prescribe a polluter any action, rather it enforces the responsibility for consequences.

The advantages of incentive-based regulations (over prescriptive regulations) are:

- mitigated informational requirements;

- enhanced incentives to innovate;

- polluter paying for control costs as well as pollution damage; and

- equimarginal principle holds for most types of economic incentives.

The disadvantages to economic incentives are:

- difficulty in developing a regulation that efficiently and perfectly address the complexities of environmental transformation;

- administrative/bureaucratic difficulties in adjusting the level of incentives in accord with the new information;

- political challenges to instituting emission fees, as they, in essence, facilitate the wealth transfer from firms to the government.

6.4 Marketable Permits

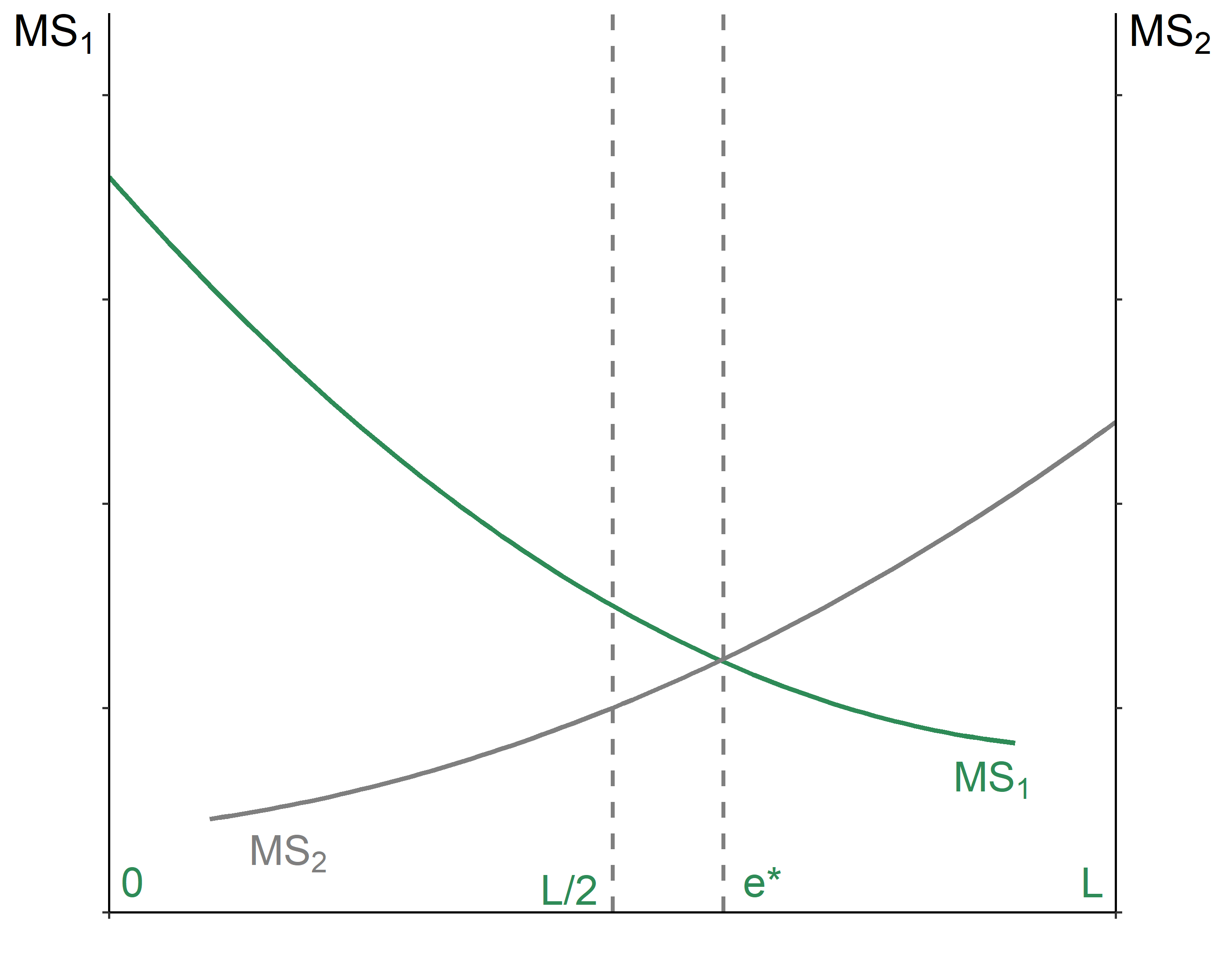

The virtue of marketable permits is that no matter how they are initially allocated, after trading, the equimarginal principle automatically holds. The following graph illustrates this.

Figure 6.1: Marketable Permits

The permits can be allocated for free, or being auctioned, with the revenue going to the government.

6.5 Emission Fees

Normally, consumer preferences for goods are communicated to producers through the price system. This system is “broken” in the case of environmental goods (or, rather, bads), because polluters’ production function does not account for the damage caused by their emissions. A way to correct this is to establish an emission fee—paid by a polluter to a regulatory entity for every unit of emission.

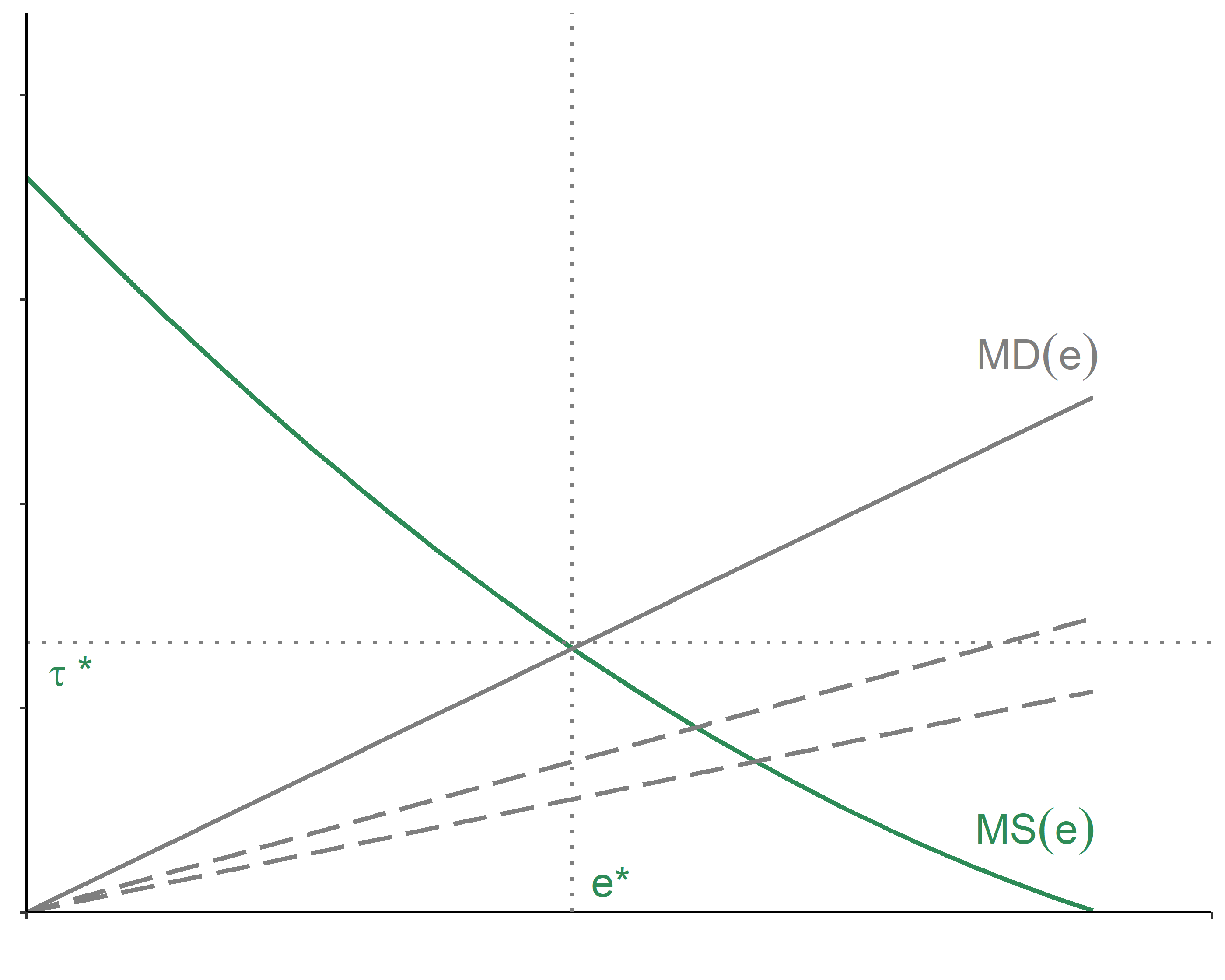

Consider a firm that produces some good, \(q\), and in the process emits pollution, \(e\). Let \(C(e)\), such that \(MC(e)<0\), denote the firm’s costs for emission abatement. That is, the firm’s costs (or efforts) to reduce pollution increase with the emission abatement. Further, let \(\tau\) be the emission fee, established by the regulator. So, the payment from the polluter to the regulator is \(\tau e\). Total emission–related costs for the firm, then, is given by the sum of the abatement costs and the payment associated with \(e\) units of emission: \[TC(e) = C(e)+\tau e.\] It then follows that at the optimum: \[\tau=-MC(e^*) \equiv MS(e^*),\] where \(MS(e)\) denotes the marginal savings from emitting one more unit of pollution.

The foregoing indicates that when faced with an emission fee, firms will abate pollution up to the point where the marginal savings (or marginal cost of abatement) is equal to the emission fee. Note that in this instance, the equimarginal principle automatically holds: each firm sets their marginal cost of abatement equal to the same emission fee.

6.6 Pigovian Taxes

A special kind of emission fee, which aims to restore Pareto optimum in the case of market failure, is known as the Pigovian tax, after the English economist Arthur C. Pigou. In particular, a Pigovian tax is an emission fee that is exactly equal to the aggregate marginal damage caused by pollution when evaluated at the optimal level of pollution.

With multiple victims of pollution, the total damage is given by the vertical sum of individual damage functions: \[D(e) = \sum_{i=1}^{n}D_i(e),\] where \(n\) denotes the total number of people who are adversely affected from the pollution emitted by a firm. The efficient amount of pollution is the amount that minimizes the sum of costs and damages from pollution. So, at the optimum: \[MD(e^*) = MS(e^*).\] The emission fee associated with this optimal level of pollution is the Pigovian tax. That is, the Pigovian tax is not just any emission fee; it is, indeed, the marginal savings from pollution at the optimal level of pollution.

Figure 6.2: Optimal Pollution

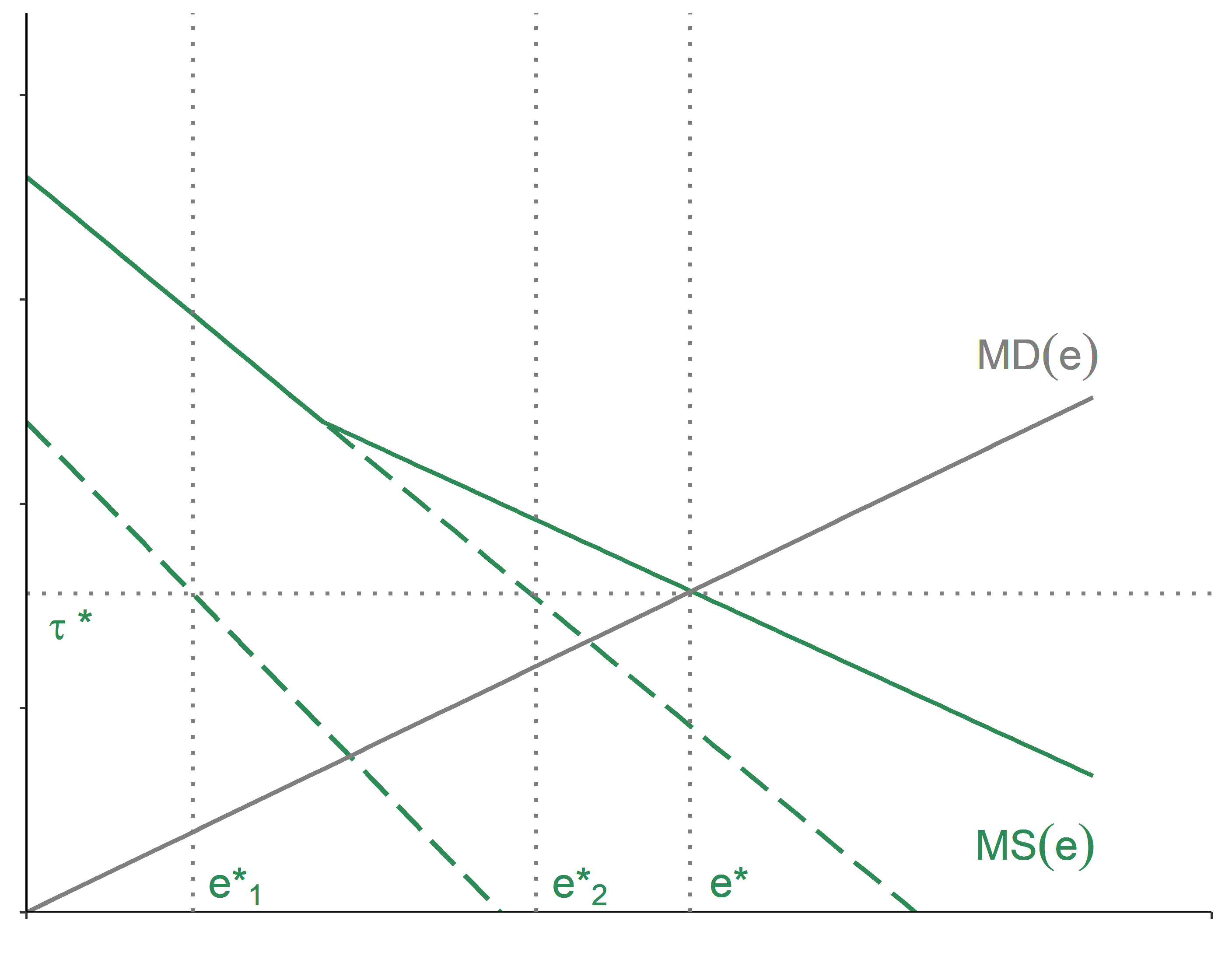

With multiple polluters, we typically assume that they are sharing the obligation of emission abatement in an efficient manner. The aggregate marginal savings is the horizontal sum of the individual marginal savings. Thus, for a given emission fee, the aggregate marginal savings tells us how much of pollution will be emitted in total, while the individual marginal savings tell us how much each firm will contribute to that total.

Figure 6.3: Optimal Pollution by Multiple Firms

References

Keohane, Mr Nathaniel O, and Sheila M Olmstead. 2016. Markets and the Environment. Island Press.

Keohane, Nathaniel O. 2009. “Cap and Trade, Rehabilitated: Using Tradable Permits to Control US Greenhouse Gases.” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 3 (1): 42–62.

Kolstad, Charles D. 2010. Environmental Economics. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.