Chapter 5 Property Rights

Kolstad (2010, Chapter 13); Keohane and Olmstead (2016, Chapter 8); Isaksen and Richter (2019)

With environmental goods, non-excludability is one of the main causes of market failure. One way to tackle the issue is by establishing property rights. This simple institutional intervention makes goods excludable, and allows markets to operate efficiently. For this to work, property rights should be well-defined, transferable, secure, and complete.

5.1 Coase and the Assignment of Rights

Who should be assigned rights: the party creating the externality (the ‘culprit’) or the party affected by the externality (the ‘victim’)? Ronald Coase raised this issue, back in 1960. Consider a case of air pollution. The problem with air pollution arises because a culprit happens to be located too close to victims. But one may also argue that a polluter is only a culprit because people who breathe polluted air happen to live too close to the polluter. So, should it be a culprit who is given the right to pollute, or should it be victims who are assigned the right to breathe clean air? Coase’s conclusion was that because the right to pollute and the right to breathe clean air are property rights that have value, as long as trade is allowed, efficiency should prevail, no matter how those rights are initially distributed.

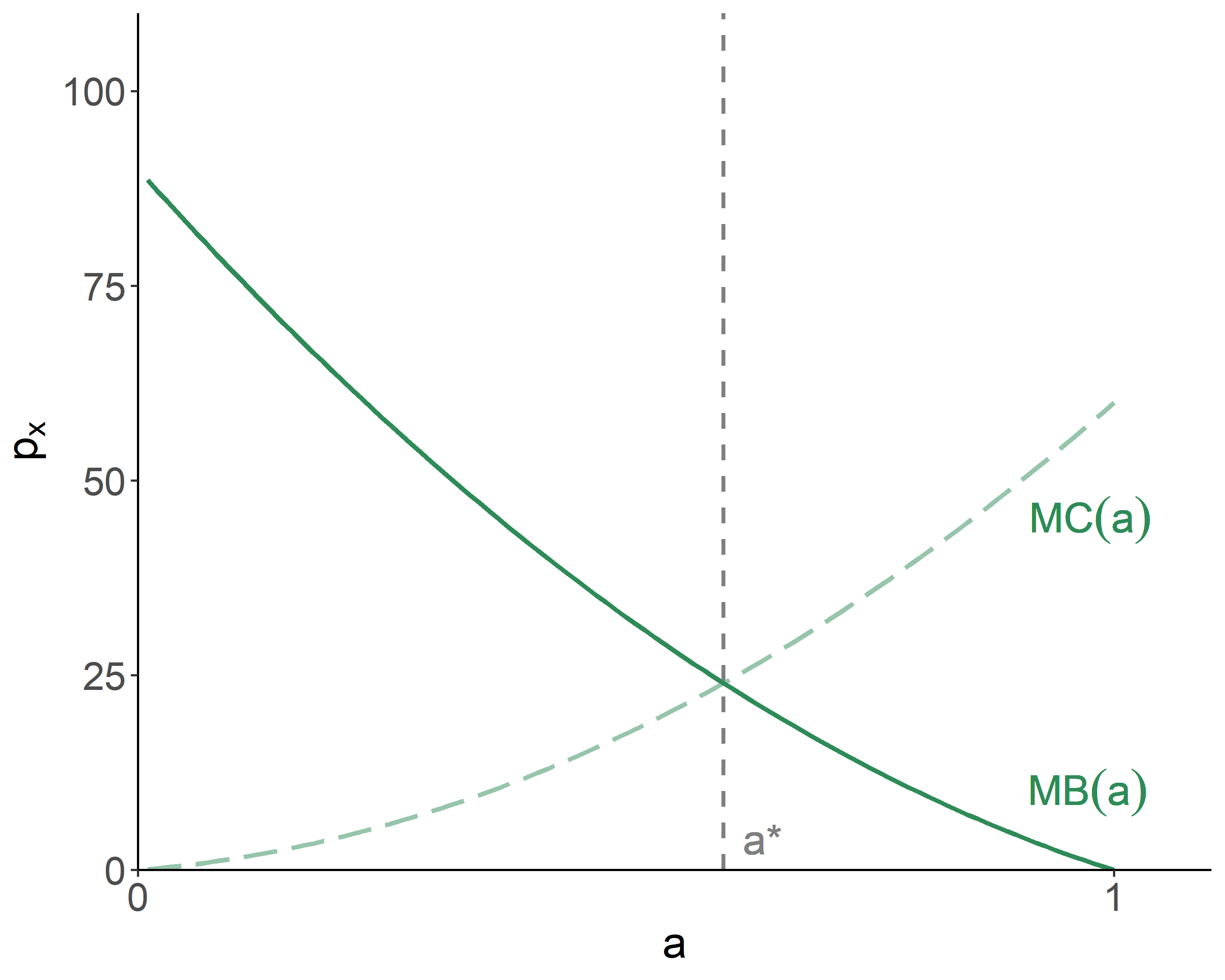

As an example, consider two firms: a steel manufacturer, which dumps the waste into the river, and a resort, which needs clean river for proper functionality. Let the firms’ profits be given by: \(\pi_s(a)\) and \(\pi_r(a)\), where \(a\) is the level of abatement which can go from 0 (no abatement) to 1 (full abatement and no pollution). The optimal level of abatement, \(a^*\), is where the marginal benefit of abatement equals the marginal costs of abatement.

Figure 5.1: Optimal Abatement

At this level, the cumulative profit is: \(\pi_s(a^*)+\pi_r(a^*)\). There are two other possible outcomes, where either one of the two facilities cease to operate. In those instances, the cumulative profit will simply be the profit of one or the other businesses—i.e., \(\pi_s(0)\) or \(\pi_r(1)\)—that has remained open. From the efficiency standpoint, the largest total profit level dictates the action to be taken.

5.1.1 The Victim Has Rights

Suppose the resort has the legal right to clean water; that is, the right to complete abatement, \(a=1\). In this scenario, the profits of the two firms are: \(\pi_s(1)\) and \(\pi_r(1)\). If the steel manufacturer wants to pollute (produce, that is), it will have to compensate the resort for any damage. That is, the resort’s profit is guaranteed to be at least \(\pi_r(1)\). At \(a=1\) the marginal cost of abatement exceeds the marginal benefit, so there is room for negotiation to reduce the abatement level.

In fact, the abatement will end up at \(a^*\), where the marginal cost of abatement equals the marginal benefit. The steel manufacturer has the following options:

- Operate and emit at \(a^*\), in which case the steel manufacturer pays the resort an amount of \(\pi_r(1)-\pi_r(a^*)\). This leaves the steel manufacturer with profits of \(\pi_s(a^*)-[\pi_r(1)-\pi_r(a^*)]\).

- Operate and emit at \(a=0\), in which case the steel manufacturer buys out the resort and shuts it down; it pays \(\pi_r(1)\) for the resort. This leaves the steel manufacturer with the remaining profit of \(\pi_s(0)-\pi_r(1)\).

- Go out of business, in which case its profits drop to zero.

The resulted steel manufacturer’s profits in the three scenarios are identical to those discussed previously except that each profit is lower by the amount of \(\pi_r(1)\). The steel manufacturer will take the action that results in the highest profit. The end result will be the same as before.

5.1.2 The Culprit Has Rights

Suppose the steel manufacturer has the legal right to pollute; that is, the right to no abatement, \(a=0\). In this scenario, the profits of the two facilities are: \(\pi_s(0)\) and \(\pi_r(0)\). If the resort wants less pollution, it will have to compensate the steel manufacturer for its reduction of profits due to the abatement. The steel manufacturer’s profit is thus guaranteed to be at least \(\pi_s(0)\).

As previously, the abatement will end up at \(a^*\), where the marginal cost of abatement equals the marginal benefit. The resort’s options are as follows:

- Operate at \(a^*\), in which case the resort pays the steel manufacturer an amount of \(\pi_s(0)-\pi_s(a^*)\), leaving the resort with remaining profits of \(\pi_r(a^*)-[\pi_s(0)-\pi_s(a^*)]\).

- Operate at \(a=1\), in which case the resort pays \(\pi_s(0)\) and buys out the steel manufacturer. This leaves the resort with remaining profits of \(\pi_r(1)-\pi_s(0)\).

- Go out of business, in which case its profits drop to zero.

The resulted resort’s profits in the three scenarios are identical to those discussed originally except that each profit is lower by the amount of \(\pi_s(0)\). The resort will take the action that results in the highest profit. The end result will be the same as in previous two cases. That is, the outcome is independent of how property rights are assigned.

5.2 The Coase Theorem

The foregoing discussion suggests that the pollution problem can be resolved as long as the involved parties are in a position to negotiate, no matter how property rights are assigned. The bargaining, between the two parties, was assumed to be easy. But this may not always be the case. It may be difficult to reach the consensus, when there are many culprits or victims (or both).

Coase’s theorem states that efficiency (socially optimal equilibrium) can be achieved in the presence of an externality, regardless of the initial assignment of property rights, under the assumptions of:

- perfect information;

- profit-maximizing producers / utility-maximizing consumers;

- price-taking economic agents;

- costless enforcement of rights;

- no income or wealth effects;

- no transaction costs.

Transaction costs are the costs incurred during an economic exchange of a good, above and beyond the price paid for the good. The zero transaction costs is a crucial assumption of the Coase Theorem. In most real world situations, there are significant transaction costs, which limits the practical application of the Coase Theorem. When transaction costs are present, it does matter where the rights are initially vested.

If the transaction costs (e.g., legal fees) exceeded the gains from bargaining, then transaction would not have taken place, and either the steel manufacturer would need to excessively abate pollution, or the resort would be burdened with excessive pollution.

5.3 Free-Riding

Bargaining is easy between two parties, but becomes exceedingly difficult as the number of parties increase. The issue is further amplified by the public bad nature of most pollution. Moreover, damage to victims is often private information, which creates incentives of free-riding.

Consider the steel manufacturer that is also a polluter, and a number of individuals who live nearby and are thus suffering from pollution. In a scenario where the steel manufacturer is assigned the rights to pollute, the individuals would need to offer a lump sum payment to the manufacturer to abate pollution. For bargaining to make sense, this payment amount should at least be equal to the costs of abatement. The payment amount, in turn, is collected from (and thus split among) the affected individuals.

But some (free-riders) may pretend that they are not affected, in which case the total payment is divided among the remaining individuals. This will increase each individual’s contribution, possibly to that point that it exceeds the perceived damage from pollution, and the Coasian solution to the pollution problem will not be reached.

In an alternative scenario where the individuals have the right to clean water, the polluter will need to compensate each person their damage. But individuals may overstate this damage, in which case it will be difficult—perhaps even impossible, but certainly inefficient—to strike the deal.

References

Isaksen, Elisabeth Thuestad, and Andries Richter. 2019. “Tragedy, Property Rights, and the Commons: Investigating the Causal Relationship From Institutions to Ecosystem Collapse.” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 6 (4): 741–81.

Keohane, Mr Nathaniel O, and Sheila M Olmstead. 2016. Markets and the Environment. Island Press.

Kolstad, Charles D. 2010. Environmental Economics. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.