Chapter 4 Market Failure

Kolstad (2010, Chapter 5); Keohane and Olmstead (2016, Chapter 5)

In a competitive market, the interaction of market demand and supply curves results in the equilibrium price and quantity that are Pareto optimal (the first theorem of welfare economics). That is, no other price–quantity combination can yield a larger total surplus than that presented by the competitive equilibrium. Moreover, in a competitive market, a Pareto optimal equilibrium can be achieved, provided that initial endowments are appropriately distributed (the second theorem of welfare economics).

The competitive equilibrium does not always yield the socially optimal price–quantity combination, however. The reasons for this could be linked with concepts known as externality, common property, and public goods.

4.1 Externality

In unregulated markets, firms’ costs typically do not account for the environmental damages (e.g., pollution)—usually associated with the production process—the supply is shifted outward compared to the socially optimal supply. That the market supply is not the same as the socially optimal supply is because of externalities. Externality is an effect of an action of one party on the utility or production function of another party without that party’s permission or compensation.

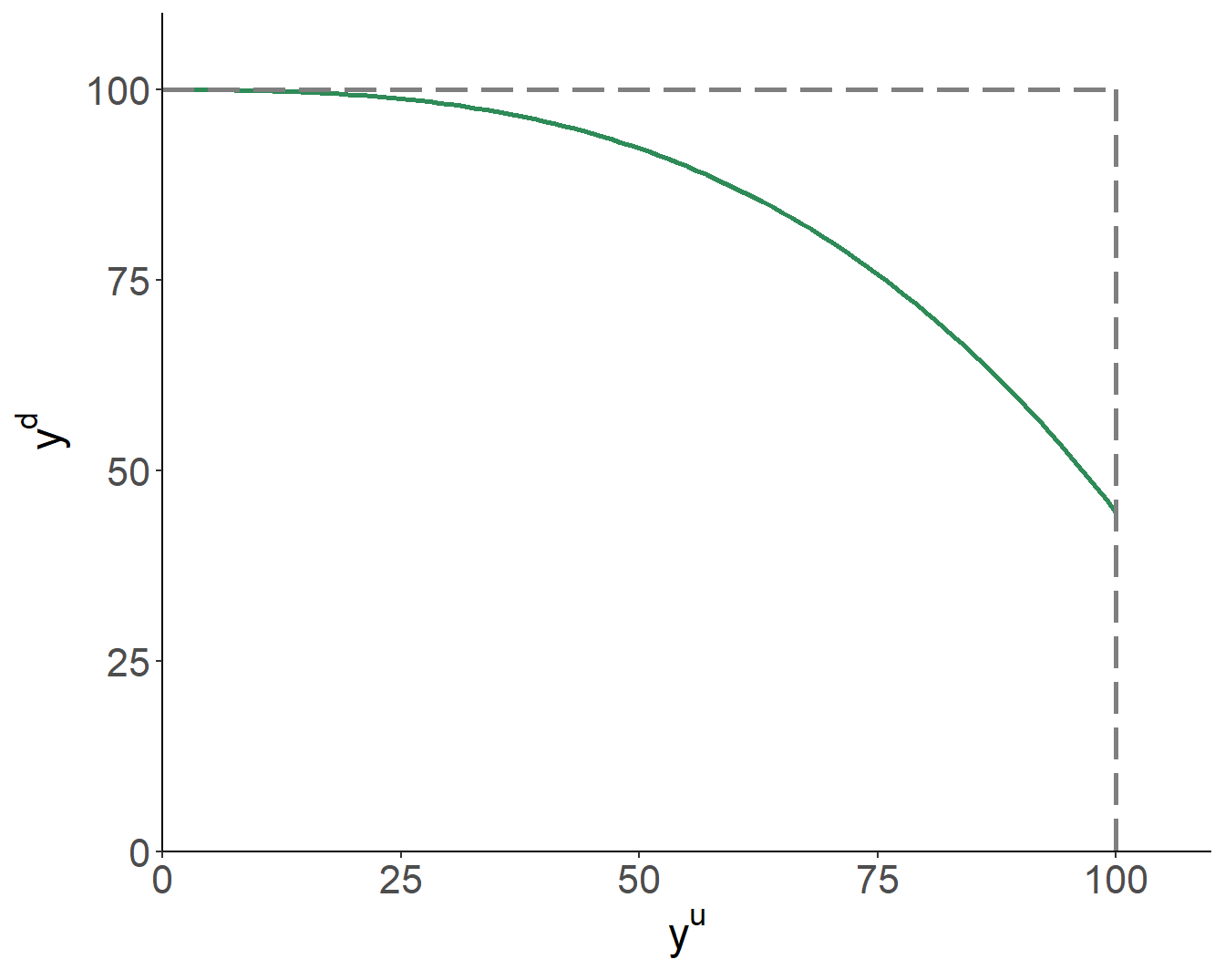

Consider two firms that are located near a river: a steel factory (upstream), which dumps the waste into the river, and a resort (downstream), which uses river for recreation. In absence of externality, the outputs of these two firms (\(y^u\) and \(y^d\)) are independent of each other. With externality, which is the waste from the steel factory, \(y^d\) can be seen as a decreasing function of \(y^u\). A production externality exists when profits of one firm are (involuntarily) affected by those of another.

Figure 4.1: Production Externality

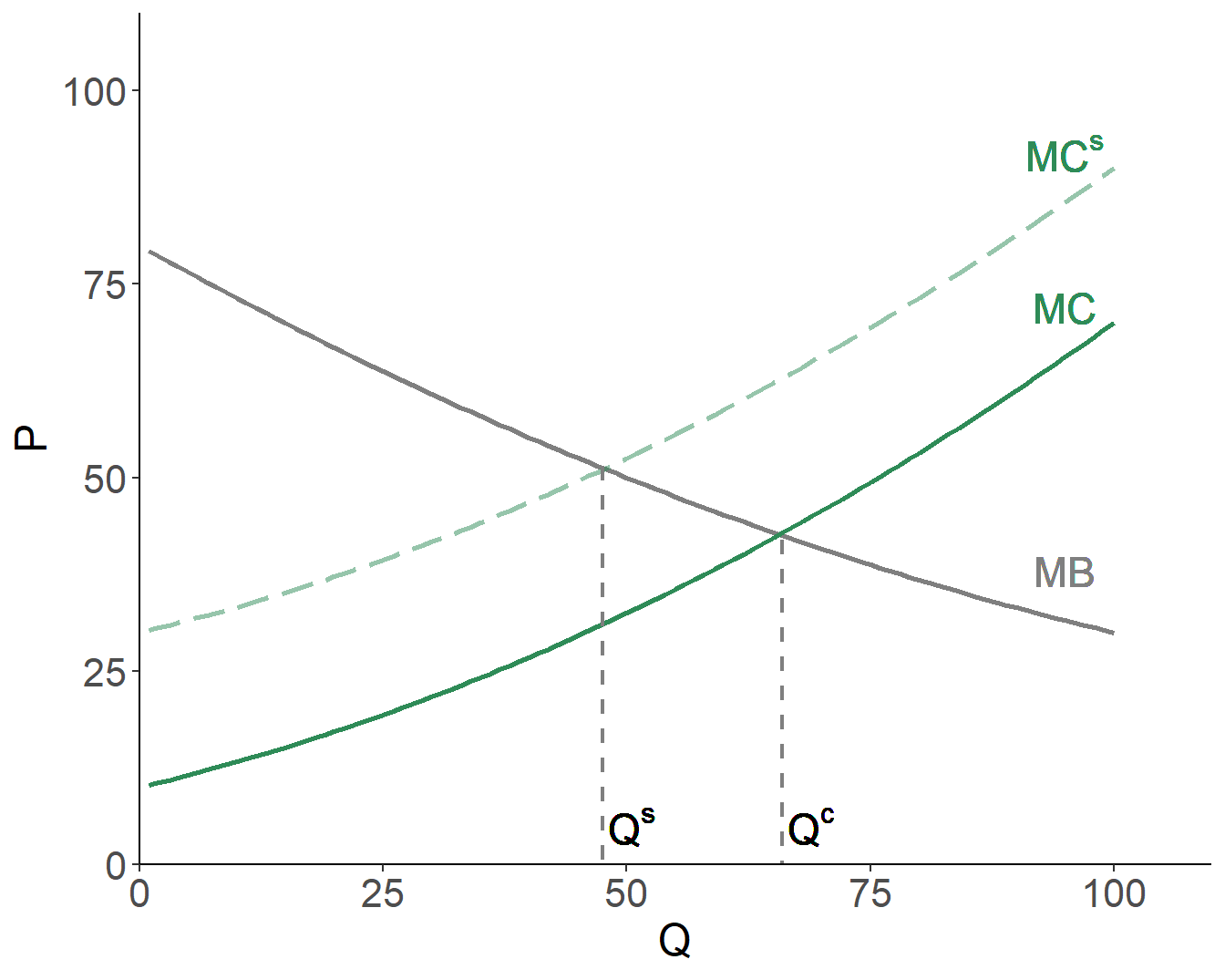

A way to resolve the issue of the externality is to make it part of the producer’s cost function. Recall that the efficient quantity of production/consumption is the quantity at which demand (which is, indeed, marginal benefit) is equal to supply (i.e., marginal cost). This equilibrium accounts for consumers and producers, but the society also includes a ‘third party.’ Thus, we need to make a distinction between the marginal cost (of production), \(MC\), the marginal external cost, \(MC^e\); and the sum of the two, which is the marginal social cost, \(MC^s = MC+MC^e\).

The marginal external cost can be negative or positive. For negative externalities (e.g., pollution, noise), \(MC^s > MC\) (or, equivalently, \(MC^e > 0\)). The market, on its own, has a tendency to produce \(Q^c>Q^s\); that is, the market tends to lead to overproduction. In the previous example, this would be the overproduction of steel by the factory.

Figure 4.2: Negative Externality

For goods that offer positive externality, such as vaccinations, blog-posts, well-maintained front-yards, \(MC^s < MC\) (or, equivalently, \(MC^e < 0\)). The market, thus, has a tendency to produce (and consume) too little compared to the socially optimal outcome (\(Q^c < Q^s\)). In other words, when left unregulated, the market tends to lead to underproduction.

4.2 Common Property

Another reason as to why markets fail with environmental goods is that most environmental goods are open access, or common property, which leads to the potential overuse of these goods—a phenomenon referred to as the tragedy of commons. People overuse common property because they do not bear the full costs of their actions (i.e., the costs of their actions on others). For example, highways that tend to be highly congested during the rush hours; or pollution from factories that treat the airshed as everyone’s property for waste disposal.

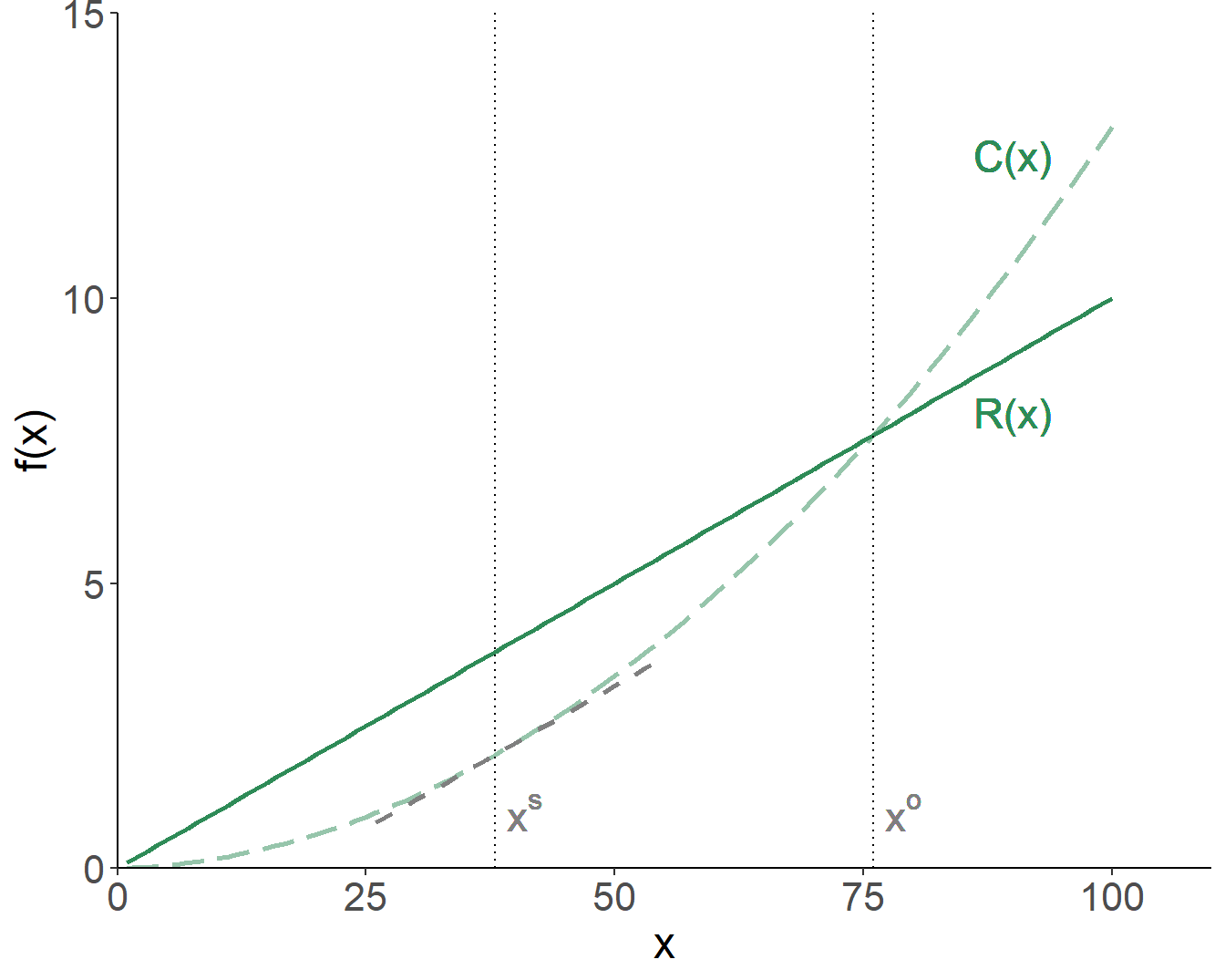

In all instances, when one person consumes the good, the marginal cost to others of consuming that good increases. To illustrate the point, consider the case of a fishery. The fish are valuable, but it takes effort to catch them. The effort is inversely proportional to the number (or density) of fish in the water. A person will engage in fishing as long as it is profitable.

Figure 4.3: The Overuse of Common Property

In this illustration, profits are exhausted at \(x^o\), even though the socially efficient amount of output is \(x^s\). The problem exists because fishermen only take into the account their individual marginal costs in their decision-making. Because people do not account for the costs of their actions on others, the common property is overused.

4.3 Public Goods (and Bads)

The important characteristic about a public good is that, once provided, many people jointly share in its benefits (e.g., clean air, highway, national defense). Public goods are not necessarily provided by the government, but they often are (and for good reason).

Two important characteristics of a public good (or bad) are excludability and rivalry.

Excludability has to do with whether it is possible to use prices to ration individual use of the good. A good is excludable if it is feasible (and practical) to selectively allow individuals to consume the good.

To be able to use prices to allocate goods, it must be possible to keep individuals from the goods, unless they have paid an appropriate price. Two factors play role in excludability: (i) the cost of exclusion, and (ii) the technology (and its evolution over time) of exclusion. Excludability enables a price system to work.

Rivalry has to do with whether it is desirable to ration individual use of the good, through prices or any other means. A good is rival if one person’s use of the good, diminishes or prevents the use of that good by others.

Based on degrees of excludability and rivalry, goods can be classified into four broad categories:

| Rival | Non-Rival | |

|---|---|---|

| Excludable | private goods | club goods |

| Non-excludable | common property | public goods |

To obtain aggregate demand, with private goods (or rival goods, more generally) we add up the demand curves horizontally, with public goods (or non-rival goods, more generally) we add up the demand curves vertically. Therefore, we cannot infer the market price for non-rival goods from the intersection of aggregate demand and supply curves—as we do so for rival goods—as the individual demands will end up being too low.

References

Keohane, Mr Nathaniel O, and Sheila M Olmstead. 2016. Markets and the Environment. Island Press.

Kolstad, Charles D. 2010. Environmental Economics. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.